I think turning everyday gadgets into bombs is a bad idea. However, recent news coverage has been framing the weaponization of pagers and radios in the Middle East as something we do not need to concern ourselves with because “we” are safe.

I respectfully disagree. Our militaries wear uniforms, and our weapons of war are clearly marked as such because our societies operate on trust. As long as we don’t see uniformed soldiers marching through our streets, we can assume that the front lines of armed conflict are far from home. When enemies violate that trust, we call it terrorism, because we no longer feel safe around everyday people and objects.

The reason we don’t see exploding battery attacks more often is not because it’s technically hard, it’s because the erosion of public trust in everyday things isn’t worth it. The current discourse around the potential reach of such explosive devices is clouded by the assumption that it’s technically difficult to implement and thus unlikely to find its way to our front door.

That assumption is wrong. It is both surprisingly easy to do, and could be nearly impossible to detect. After I read about the attack, it took half an hour to combine fairly common supply chain knowledge with Wikipedia queries to propose the mechanism detailed below.

Why It’s Not Hard

Lithium pouch batteries are ubiquitous. They are produced in enormous volumes by countless factories around the world. Small laboratories in universities regularly build them in efforts to improve their capacity and longevity. One can purchase all the tools to produce batteries in R&D quantities for a surprisingly small amount of capital, on the order of $50,000. This is a good thing: more people researching batteries means more ideas to make our gadgets last longer, while getting us closer to our green energy objectives even faster.

Above is a screenshot I took today of search results on Alibaba for “pouch cell production line”.

The process to build such batteries is well understood and documented. Here is an excerpt from one vendor’s site promising to sell the equipment to build batteries in limited quantities (tens-to-hundreds per batch) for as little as $15,000:

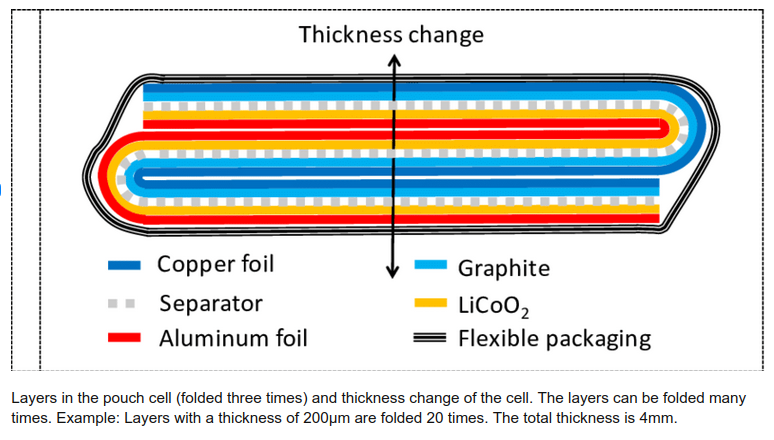

Pouch cells are made by laying cathode and anode foils between a polymer separator that is folded many times:

Above from “High-resolution Interferometric Measurement of Thickness Change on a Lithium-Ion Pouch Battery” by Gunther Bohn, DOI:10.1088/1755-1315/281/1/012030, CC BY 3.0

The stacking process automated, where a machine takes alternating layers of cathode and anode material (shown as bare copper in the demo below) and wraps them in separator material:

There’s numerous videos on Youtube showing how this is done, here’s a couple of videos to get you started if you are curious.

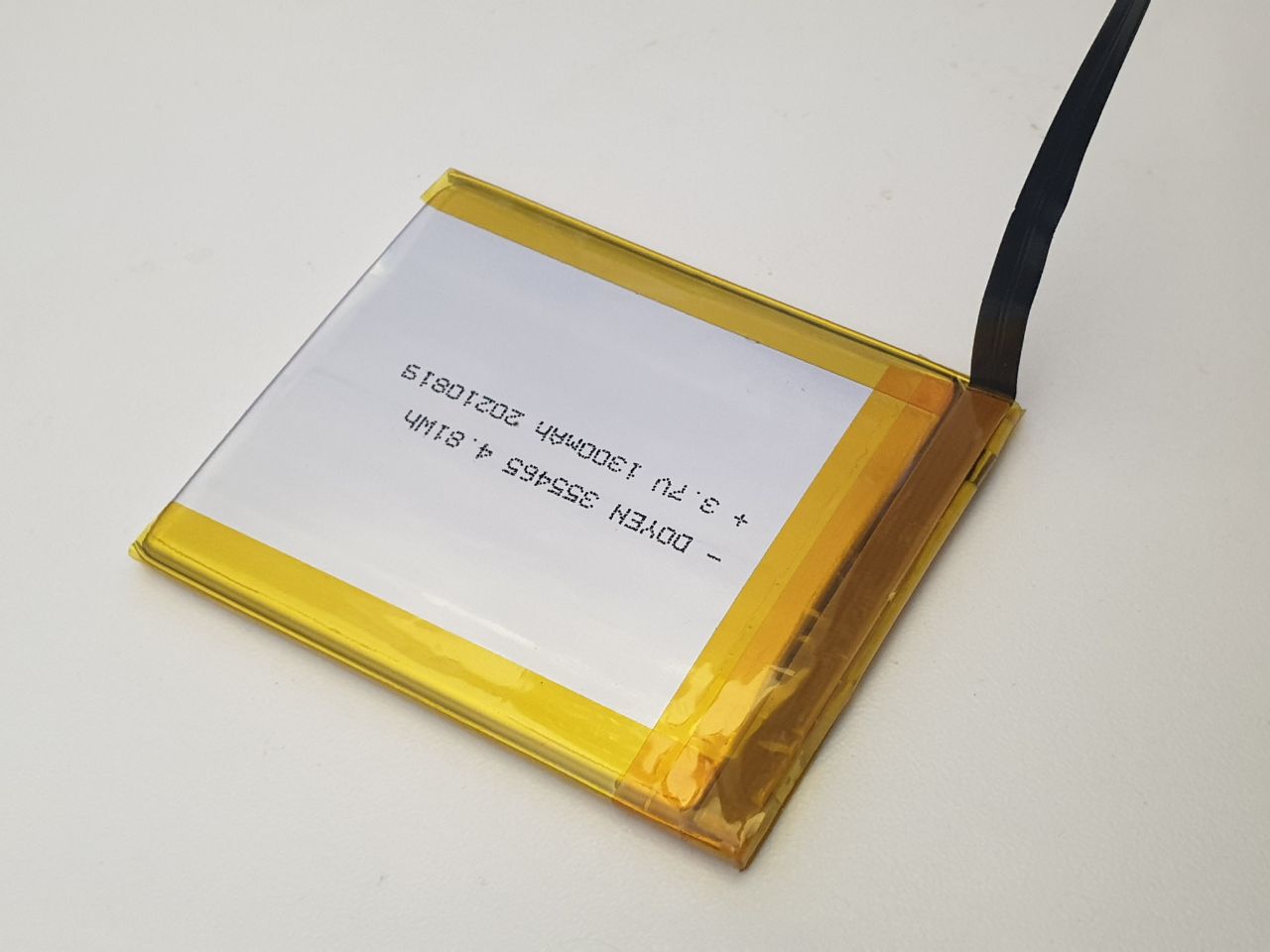

After stacking, the assembly is laminated into an aluminum foil pouch, which is then trimmed and marked into the final lithium pouch format:

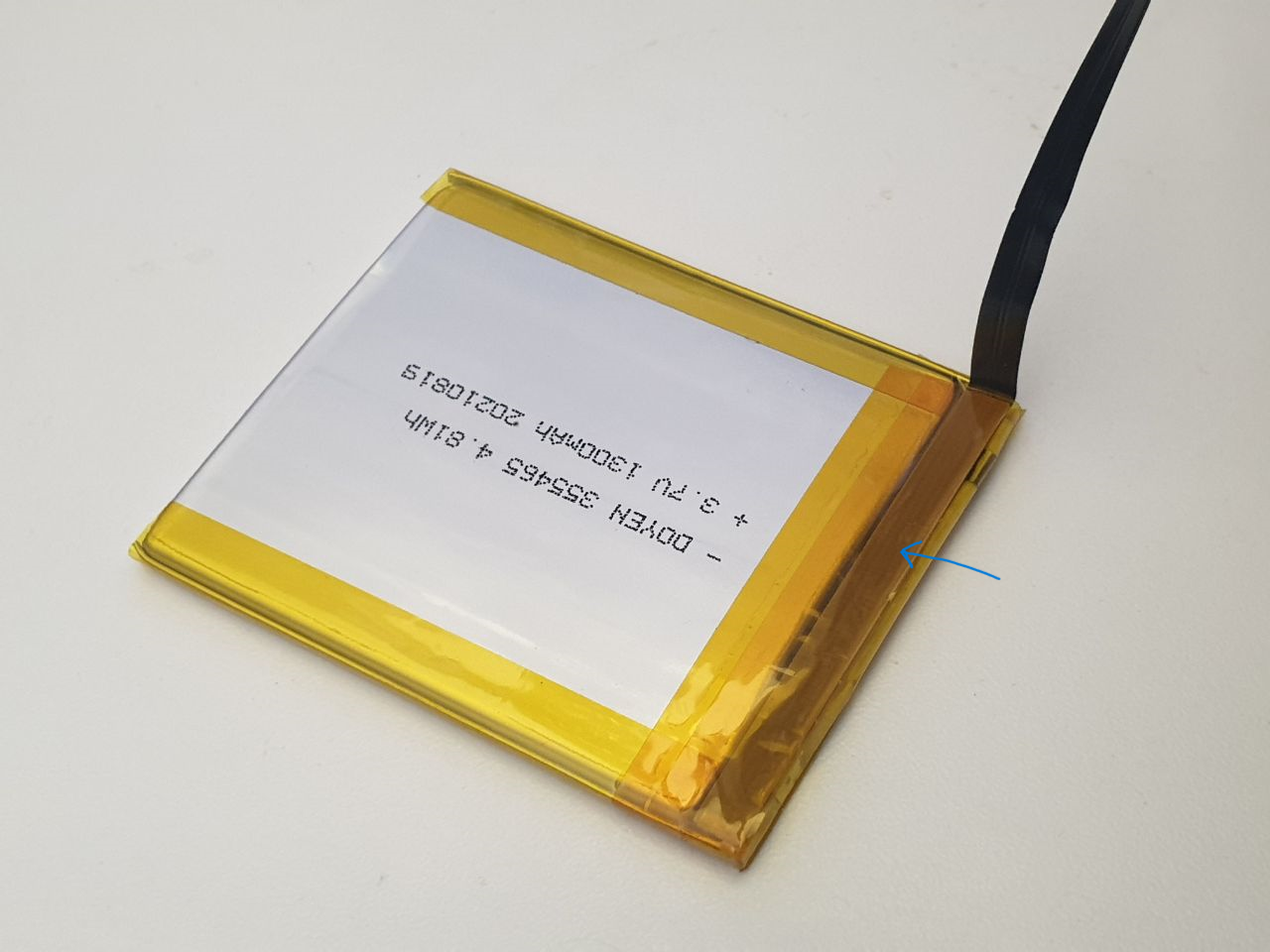

Above is a cell I had custom-fabricated for a product I make, the Precursor. It probably has about 10-15 layers inside, and it costs a few thousand dollars and a few weeks to get a thousand of these made. Point is, making custom pouch batteries isn’t rocket science – there’s a whole bunch of people who know how to do it, and a whole industry behind it.

Reports indicate the explosive payload in the cells is made of PETN. I can’t comment on how credible this is, but let’s assume for now that it’s accurate. I’m not an expert in organic chemistry or explosives, but a read-through the Wikipedia page indicates that it’s a fairly stable molecule, and it can be incorporated with plasticizers to create plastic explosives. Presumably, it can be mixed with binders to create a screen-printed sheet, and passivated if needed to make it electrically insulating. The pattern of the screen printing may be constructed to additionally create a shaped-charge effect, increasing the “bang for the buck” by concentrating the shock wave in an area, effectively turning the case around the device into a small fragmentation grenade.

Such a sheet could be inserted into the battery fold-and-stack process, after the first fold is made (or, with some effort, perhaps PETN could be incorporated into the spacer polymer itself – but let’s assume for now it’s just a drop-in sheet, which is easy to execute and likely effective). This would have the effect of making one of the cathode/anode pairs inactive, reducing the battery capacity, but only by a small amount: only one layer out of at least 10 layers is affected, thus reducing capacity by 10% or less. This may be well within the manufacturing tolerance of an inexpensive battery pack; alternatively, the cell could have an extra layer added to it to compensate for the capacity loss, with a very minor increase in the pack height (0.2mm or so, about the thickness of a sheet of paper – within the “swelling tolerance” of a battery pack).

Why It Could Be Hard to Detect

Once folded into the core of the battery, it is sealed in an aluminum pouch. If the manufacturing process carefully isolates the folding line from the laminating line, and/or rinses the outside of the pouch with acetone to dissolve away any PETN residue prior to marking, no explosive residue can escape the pouch, thus defeating swabs that look for chemical residue. It may also well evade methods such as X-Ray fluorescence (because the elements that compose the battery, separator and PETN are too similar and too light to be detected), and through-case methods like SORS (Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy) would likely be defeated by the multi-layer copper laminate structure of the battery itself blocking light from probing the inner layers.

Thus, I would posit that a lithium battery constructed with a PETN layer inside is largely undetectable: no visual inspection can see it, and no surface analytical method can detect it. I don’t know off-hand of a low-cost, high-throughput X-ray method that could detect it. A high-end CT machine could pick out the PETN layer, but it’d cost around a million dollars for one machine and scan times are around a half hour – not practical for i.e. airport security or high throughput customs screening. Electrical tests of capacity and impedance through electromechanical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) may struggle to differentiate a tampered battery from good batteries, especially if the battery was specifically engineered to fool such tests. An ultrasound test might be able to detect an extra layer, but it would require the battery to placed in intimate contact with an ultrasound scanner for screening. I also think that that PETN could be incorporated into the spacer polymer film itself, which would defeat even CT scanners (but may leave a detectable EIS fingerprint). Then again, this is just what I’m coming up with stream-of-consciousness: presumably an adversary with a staff of engineers and months of time could figure out numerous methods more clever than what I came up with shooting from the hip.

Detonating the PETN is a bit more tricky; without a detonator, PETN may conflagrate (burn fast), instead of detonating (and creating the much more damaging shock wave). However, the Wikipedia page notes that an electric spark with an energy in the range of 10-60 mJ is sufficient to initiate detonation.

Based on an available descriptions of the devices “getting hot” prior to detonation, one might suppose that detonation is initiated by a trigger-circuit shorting out the battery pack, causing the internal polymer spacers to melt, and eventually the cathode/anode pairs coming into contact, creating a spark. Such a spark may furthermore be guaranteed across the PETN sheet by introducing a small defect – such as a slight dimple – in the surrounding cathode/anode layers. Once the pack gets to the melting point of the spacers, the dimpled region is likely to connect, leading to a spark that then detonates the PETN layer sandwiched in between the cathode and anode layers.

But where do you hide this trigger-circuit?

It turns out that almost every lithium polymer pack has a small circuit board embedded in it called the PCM or “protection circuit module”. It contains a microcontroller, often in a “TSSOP-8” package, and at least one or more large transistors capable of handling the current capacity of the battery.

I’ve noted where the protection circuit is on my custom battery pack with a blue arrow. No electronics are visible because the circuit is folded over to protect the electronics from damage.

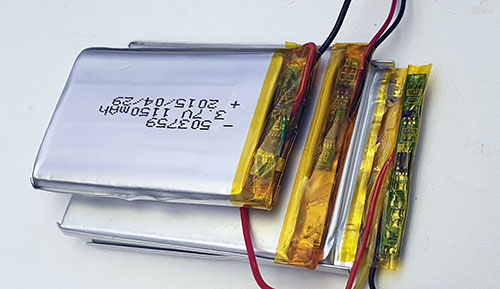

And above is a selection of three pouch cells that happen to have readily visible protection circuitry. The PCM is the thin green circuit board on the right hand side, covered in protective yellow tape. One take-away from this image is the diversity inherent in PCM modules: in fact, vendors may switch out PCM modules for functionally equivalent ones depending on component availability constraints.

Normally, the protection circuit has a simple job: sample the current flow and voltage of the pack, and if these go outside of a pre-defined range, turn off the flow of current.

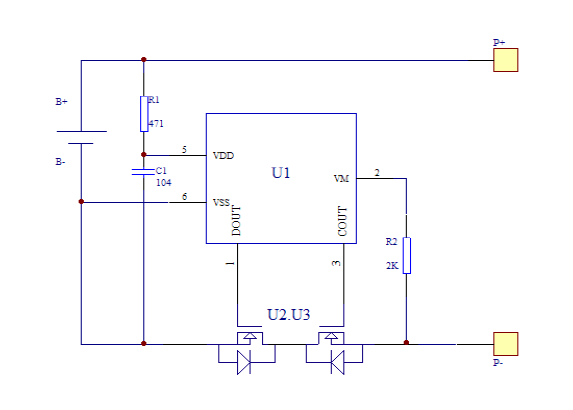

Above: Example of a protection circuit inside a pouch battery. U1 is the controller IC, while U2 and U3 are two separate transistors employed to block current flow in both directions. One of these transistors can be repurposed to short across the battery while still leaving one transistor for protection use (able to block current flow in one direction). Thus the cell is still partially protected despite having a trigger circuit, defeating attempts to detect a modified circuit by simply counting the number of components on the circuit board, or by doing a simple short-circuit or overvoltage test.

A small re-wiring of traces on the protection circuit board gives you a circuit that instead of protecting the battery from out-of range conditions, turns it into a detonator for the PETN layer. One of the transistors that is normally used to cut the flow of electricity is instead wired across the terminals of the battery, allowing for a selective short circuit that can lead to the melting of the spacer layers, ultimately leading to a spark between the dimpled anode/cathode layers and thus detonation of the PETN.

The trigger itself may come via a “third wire” that is typically present on battery packs: the NTC temperature sensor. Many packs contain a safety feature where a nominally 10k resistor is provided to ground that has a so-called “negative temperature coefficient”, i.e., a resistance that changes in a well-characterized fashion with respect to temperature. By measuring the resistance, an external controller can detect if the pack is overheating, and disconnect it to prevent further damage.

However, the NTC can also be used as a one-wire communication bus: the controller IC on the protection circuit can readily sample the voltage on the NTC wire. Normally, the NTC has some constant positive bias applied to it; but if the NTC is connected to ground in a unique pattern, that can serve as a coded trigger to detonate.

The entirety of such a circuit could conceivably be implemented using an off-the-shelf microcontroller, such as the Microchip/Atmel Attiny 85/V, a TSSOP-8 device that would look perfectly at-home on a battery protection PCB, yet contains an on-board oscillator and sufficient code space such that it could decode a trigger pattern.

If the battery charger is integrated into the main MCU – which it often is in highly cost-reduced products such as pagers and walkie-talkies – the trigger sequence can be delivered to the battery with no detectable modification to the target device. Every circuit trace and component would be where it’s supposed to be, and the MCU would be an authentic, stock MCU.

The only difference is in the code: in addition to mapping a GPIO to an analog input to sample the NTC, the firmware would be modified to convert the GPIO into an output at “trigger time” which would pull the NTC to ground in the correct sequence to trigger the battery to explode. Note that this kind of flexibility of pin function is quite typical for modern microcontrollers.

Technical Summary

Thus, one could conceivably create a supply chain attack to put exploding batteries into everyday devices that is undetectable: the main control board is entirely unmodified; only a firmware change is needed to incorporate the trigger. It would pass every visual and electrical inspection.

The only component that has to be swapped out is the lithium pouch battery, which itself can be constructed for an investment as small as $15,000 in equipment (of course you’d need a specialist to operate the equipment, but pouch cells are ubiquitous enough that it would not be surprising to find a line at any university doing green-energy research). The lithium pouch cell itself can be constructed with an explosive layer that I hypothesize would be undetectable to most common analytical methods, and the detonator trigger can be constructed so that it is visually and mostly electrically indistinguishable from the protection circuit module that would be included on a stock lithium pouch battery, using only common, off-the-shelf components. Of course, if the adversary has the budget to make a custom chip, they could make the entire protection circuit perfectly indistinguishable to most forms of non-destructive inspection.

How To Attack a Supply Chain

Insofar as how one can get such cells and firmware updates into the supply chain – see any of my prior talks about the vulnerability of hardware supply chains to attack. For example: this talk which I gave in Israel in 2019 at the BlueHat event, outlining the numerous attack surfaces and porosity of modern hardware supply chains.

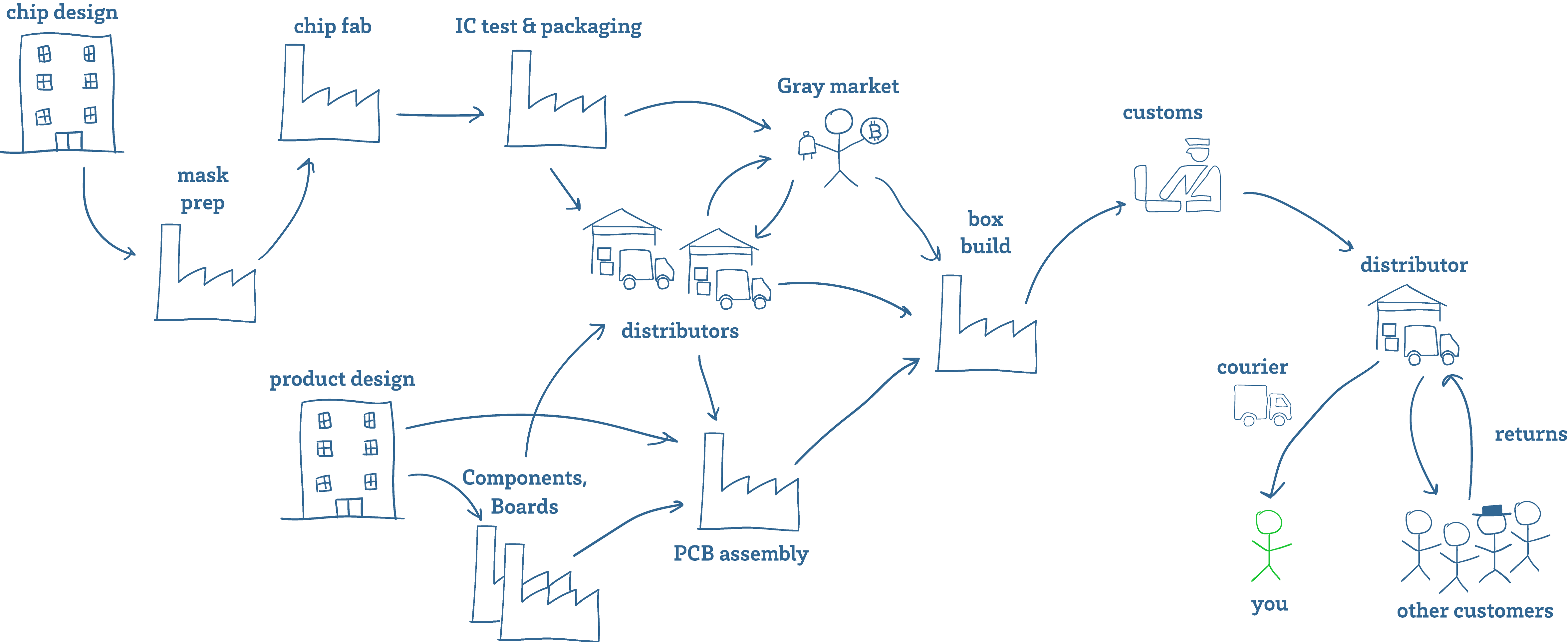

Above is a cartoon sketch of a supply chain. Getting fake components into the supply chain is easier than you might think. As a manufacturer of hardware, I have to deal with fake components all the time. This is especially true for batteries – most popular consumer electronic devices already have a healthy gray market for replacement batteries. These are batteries that look the same as OEM batteries and fetch an OEM price, but are made with sub-par components.

Aside from taking advantage of gray and secondary markets, there are multiple opportunities along the route from the factory to you to tamper with goods – from the customs inspector, to the courier.

But you don’t even have to go so far as offering anyone a bribe or being a state-level agency to get tampered batteries into a supply chain. Anyone can buy a bunch of items from Amazon, swap out the batteries, restore the packaging and seals, and return the goods to the warehouse (and yes, there is already a whole industry devoted to copying packaging and security seals for the purpose of warranty fraud). The perpetrator will be long-gone by the time the device is resold. Depending on the objective of the campaign, no further targeting may be necessary – just reports of dozens of devices simultaneously detonating in your home town may be sufficient to achieve a nefarious objective.

Note that such a “reverse-logistics injection attack” works even if you on-shore all your factories, and tariff the hell out of everyone else. Any “tourist” with a suitcase is all it takes.

Pandora’s Box is Open

Not all things that could exist should exist, and some ideas are better left unimplemented. Technology alone has no ethics: the difference between a patch and an exploit is the method in which a technology is disclosed. Exploding batteries have probably been conceived of and tested by spy agencies around the world, but never deployed en masse because while it may achieve a tactical win, it is too easy for weaker adversaries to copy the idea and justify its re-deployment in an asymmetric and devastating retaliation.

However, now that I’ve seen it executed, I am left with the terrifying realization that not only is it feasible, it’s relatively easy for any modestly-funded entity to implement. Not just our allies can do this – a wide cast of adversaries have this capability in their reach, from nation-states to cartels and gangs, to shady copycat battery factories just looking for a big payday (if chemical suppliers can moonlight in illicit drugs, what stops battery factories from dealing in bespoke munitions?). Bottom line is: we should approach the public policy debate around this assuming that someday, we could be victims of exploding batteries, too. Turning everyday objects into fragmentation grenades should be a crime, as it blurs the line between civilian and military technologies.

I fear that if we do not universally and swiftly condemn the practice of turning everyday gadgets into bombs, we risk legitimizing a military technology that can literally bring the front line of every conflict into your pocket, purse or home.

Pandora’s box has been open. I fear the future as this proliferates now.

You could also implement triggering without the TEMP terminal: by monitoring the current and waiting for a particular sequence (à la 4-20 current loop signalling).

So It was necessary to modify the firmware to generate the pulsed current sequence. The malware injection could have been made by a US military aircraft designed specifically for electronic warfare, the EC-130H Compass Call. Two of those planes (rarely observed) were detected off the coast of Lebanon 19h prior to the attack: they could have pushed an OTA firmware update to the pagers.

It’s not too hard to envision how to trigger the explosion without modifying the firmware at all, given that the battery has the ability to monitor how much current is being drawn. Think “port knocking.”

It was a very interesting hack, but it belongs in a Batman movie rather than in a city full of non-combatants. Obviously there will be at least a few duds that won’t explode at the right time, even if you believe that there *is* a right time, but may kill or maim innocent people in the future.

[…] 详情参考 […]

“Turning everyday objects into fragmentation grenades should be a crime, as it blurs the line between civilian and military technologies.”

It _is_ a crime. Or at least, it is illegal according to https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/ccw-amended-protocol-ii-1996/article-7

Article 7 – Prohibitions on the use of booby-traps and other devices, art. 2:

It is prohibited to use booby-traps or other devices in the form of apparently harmless portable objects which are specifically designed and constructed to contain explosive material.

And most nations are signatories of the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) Protocol II, including Israel and USA

That’s funny, because shooting thousands of rockets at Israel is hardly a gesture of peace!

Unfortunately those laws are meaningless when they aren’t enforced, as we’ve all seen recently

It would appear that it already is illegal, subject to questions about anticipated military advantage and proportionality of harm.

https://lieber.westpoint.edu/exploding-pagers-law/

For all the bravado that is attributed to the IDF/Mossad/Unit8200, they failed to think of the consequences. Like you said, we work and live in a world of trust. I don’t expect my laptop to explode (unless the system failed but not because it was compromised).

Like the various conventions on warfare norms (sounds oxymoronic, but it exists), we cannot normalize such behaviour. The US would not stop Israel from continuing such tactics – the global military industrial complex is too ingrained for that to happen.

We need more people to understand technology, understand how everyday things work and not be throwing up arms and saying “I don’t know how this works and it is too hard”.

Thanks, Bunnie for the excellent post. I learned a lot from it.

This is proper horrifying, and I’m not excited for the 2020s and 2030s new terrorism/mass killing tactics we’ll be subject to until this is fixed.

I wish we had replaceable battery standards for everyday items, so that I didn’t have to trust new batteries/could bring them to an explosives range for testing

It’s looking like method for supply chain compromise was to set up fake companies to sell the booby-trapped pagers/walkie-talkies that IDF manufactured. No interception required.

Sounds like IDF conned a Taiwanese manufacturer into a “white label” deal to slap the manufacturer’s branding on IDF’s pagers.

The walkie-talkies were counterfeits of a Japanese model that was discontinued a decade ago.

See

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/18/world/middleeast/israel-exploding-pagers-hezbollah.html

and

https://www.timesofisrael.com/israeli-spies-behind-hungarian-firm-that-was-linked-to-exploding-pagers-report/

> Turning everyday objects into fragmentation grenades should be a crime, as it blurs the line between civilian and military technologies.

Indeed. It’s also not surprising the first of this crime has came out of Israel. One state should not feel that free to achieve its religious goals by any means.

Any mandarin (or cantonese?) reader here? Does this video have any new information?

https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1GbtGeSE5H/

It shows the (Apollo AR-924?) PCB

I understand that what happened in Libanon was that dedicated explosives were added to the devices, it was not the batteries exploding. But that does not take away the conclusion of your story.

As much as I hate the IDF and its current war on all non-complicit arabs, this was a genius attack.

Dare I say a genius terrorist attack.

Israel is capable of using disinfo to get hezbollah scared into using pagers, and then supplying them via taiwan and BAC Consulting (Hungary), then how am I supposed to believe they can’t avoid killing kids with bombs?

[…] não uma suposta dificuldade técnica — que, como ele explica, não existe. / bbc.com, bunniestudios.com (em […]

Very good article.

Without your knowledge and from a more abstract point of view, I thought that the firmware update can be skipped analyzing power consumption. The trigger event could be a sequence of time spaced messages or exploiting a vulnerability in the firmware.

I’ve sketched this idea in my website seguridad-agile[dot]blogspot.com/2024/09/pager-bomb[dot]html

FOUCAULT’S BOOMERANG

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_boomerang

[…] fuck-yous blew open Pandora’s box — and then […]

Good article! This is very scary obviously. But from what I’ve read, the amount of PETN in the pagers had to be several grams (if not tens of grams) to cause this much trauma. But a battery like you used as example weighs 10-20 grams, so adding/replacing one sheet would add at the very best 1 gram of PETN, and likely much less than one gram. So this type of attack would need to deploy much much larger batteries to be effective. (This is not to say that even a very small explosion couldn’t cause widespread panic)

Good article, this nefarious technology is really the tip of the iceberg. One final thought; “Turning Everyday Gadgets into Bombs is a Bad Idea” bunny states as the directions are posted on the internet.

Killers (national, religious, cultural, personal) are by default sociopaths. Don’t expect them to cooperate. Fixing this first requires recognition of this fact:

I sense a sudden explosion (no pun intended) in supply chain security services.

[…] Turning Everyday Gadgets into Bombs is a Bad Idea « bunnie's blog […]

An excellent article, thank you! :)

As some 12-dimensional chess, I’ll cautiously argue that “turning everyday gadgets into bombs is a *good* idea”, despite being obviously harmful to every person in this conversation, and being a war crime.

We’ve much bigger problems than the weapons with which people fight, notably climate change.[1] Also, climate change seemingly ranks only fourth among the six transgressed planetary boundaries. We’re really fucking ourselves over through out world economy.

Air travel is a global disaster for multiple reasons. Air travel is basically impossible to decarbinize well. Air travel acts as a “trust” engine that maintains exploitive empires, especially multi-national corporations: https://phe.rockefeller.edu/docs/empires_booklet.pdf These empires are de facto leading our transgression of planetary boundaries like climate.

Israel is economically irrelevant, ditto random “terrorists”. Airlines & regulators would react if phone attacks were used by a major player, like Russia in Ukraine, or the US in Venezuela or wherever, or China in Taiwan. It’s likely they’d make flying much more difficult, maybe requiring removable batteries, maybe background checks, etc. Air travel would not disapear just because phones ocasionally explode, but related economic complexities c ould speed up the effects of peak oil somehow.

Air travel dying out a decade sooner would humanity on the whole.

[1] Climate change is far more dangerous than even nuclear war. In recent years, Canadian wildfires have typically burnned enough area that the hot soot released should correspond to a nuclear war of more than 2000 Mt, computed by applying one of Toon’s approximations in reverse. Anderson’s models say climate change shall cause nuclear summer, likely for more than the 15 years of a nuclear war.

With all due respect Bunnie, these were not “everyday gadgets”. These were gadgets specifically used by a terrorist militia, not something that can be purchased OTC by you, me or any lebanese down in Beirut.

Great analysis. It’s terrifying just how easily such terror attacks can be executed. Technology proliferation makes humans and social structures appear ever more fragile as time goes on. It’s hard to see this trend reversing. Hoping that everyone will view the cost of using these weapons as outweighing the benefit feels tenuous. But in the face of continuous technological advancement, there seems to be no other solution than to create a global economic order that gives most, if not all, individuals a reason to believe in equality and the benefits of cooperation.

I visited Singapore recently, and feel like I glimpsed a piece of this intangible future while there. Beautiful public spaces, efficient transit, a super-dense central business district, and most interesting of all: enormous quantities of public housing. The theme always seemed to be the effective application of the common property for common uses. Unlike in California, I saw very little vacant or underused land, and also nobody who was homeless or destitute. All of society’s members seemed have access to land for living and production. Everyone coexisted well despite cultural diversity and language barriers.

It’s no coincidence that the these pager bombs were deployed in the latest flare-up of a long and protracted war over land where one population rapidly dispossessed another population. The conflict fundamentally stems from the unequal distribution of a scarce resource. Only an integrated society that captures and equally redistributes the value of the land, thus ensuring every member always has equal access to the land value, can truly achieve stability. In this regard, Singapore provides perhaps the best developed model.

The fact that the Islamist side is totally divided, and has shown no success finding a single organisation to carry their case forward has been their fatal story!

[…] Turning Everyday Gadgets into Bombs is a Bad Idea. Breakdown of a breakdown in trust. […]

[…] read Bunnie Huang’s essay on what it means to live in a world where people can turn IoT devices into bombs. His […]

[…] read Bunnie Huang’s essay on what it means to live in a world where people can turn IoT devices into bombs. His […]

[…] read Bunnie Huang’s essay on what it means to live in a world where people can turn IoT devices into bombs. His […]

[…] read Bunnie Huang’s essay on what it means to live in a world where people can turn IoT devices into bombs. His […]

[…] read Bunnie Huang’s essay on what it means to live in a world where people can turn IoT devices into bombs. His […]

Here is a follow-up article on how the exploding pagers were made and the extensive backstory required to thwart Hezbollah’s due dilligence. The claim it that it was not a simple foil pouch play.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/how-hezbollah-was-fooled-into-purchasing-explosive-pagers/

[…] read Bunnie Huang’s essay on what it means to live in a world where people can turn IoT devices into bombs. His […]

[…] Huang leaves us with the terrifying realization that constructing a bomb right into a small IoT system isn’t simply possible—it’s comparatively straightforward and […]

[…] Huang meninggalkan kita dengan kesadaran yang menakutkan akan hal itu membuat bom menjadi perangkat IoT kecil tidaklah mungkin dilakukan—itu relatif mudah dan […]

[…] Huang leaves us with the terrifying realization that building a bomb into a small IoT device isn’t just feasible—it’s relatively easy and […]

[…] Huang leaves us with the terrifying realization that constructing a bomb right into a small IoT machine isn’t simply possible—it’s comparatively simple and […]

[…] Huang leaves us with the terrifying realization that constructing a bomb right into a small IoT system isn’t simply possible—it’s comparatively straightforward and […]

[…] Huang leaves us with the terrifying realization that constructing a bomb right into a small IoT system isn’t simply possible—it’s comparatively straightforward and […]

[…] Huang leaves us with the terrifying realization that building a bomb into a small IoT device isn’t just feasible—it’s relatively easy and […]

I don’t know how much you know about statistical quality control. If you’re never studied industrial engineering, you might not know about it. The basic principle is that you take a random sample of mass-produced objects, and test them to destruction, using the Poisson probability tables to determine an acceptable sample size. Having chosen your sample, you test it to destruction. A lot of explosives, heated to boiling point, explode spontaneously.

You adjust the sample size, increasing it after a batch fails, or according to perceived risks.

To take the example of the pagers, 10% testing to destruction is acceptable. It only increases the net price by 11%. On the other side, 1% explosive pagers would be acceptable— that’s well within the general risks of war. Say you buy a lot of 10,000 batteries. That means you test 1000 to destruction, expecting 10 explosions.

Per the Poisson Table, the probability of zero explosions in the sample is <0.0001.

Warfighting with the modified consumer products, from drones to exploding pagers, *is* something novel. It is worth discussing.

Starting with this chilling “IoT” play, the “domino effect” of Hesbollah’s cease-fire, a humbled Persia, and the fall of Syria, has brought the Middle East closer to peace than we’ve seen in the last 50 years. It’s tough living next door to militants. Let’s hope this all lead to sincere coexistence. Next: successful diplomacy towards the ever-elusive “two-state solution.” This will be much harder than blowing stuff up, as none of the parties are “of one mind.”

Food for thought: Are exploding pagers more or less scary than Stuxnet?

[…] the device's internal structure before taking action. Modern detection faces challenges with battery-based explosives that can be concealed within everyday […]