Amendment 1092 to the Defense Authorization Act of 2012 is a well-intentioned but misguided provision outlining measures designed to reduce the prevalance of counterfeit chips in the US military supply chain.

The Defense Authorization Act already has drawn flack for a provision that gives the US military authorization to detain US citizens indefinitely without trial, and I think it rather ironically requires an assessment of the US Federal Debt owed China as a potential “National Security Risk” (section 1225 of HR1540) — anyone want to take bets as to whether the conclusion of this assessment leads to prioritizing deficit reduction as a national security issue, or if it leads to justifying further borrowing from China to build up a military to fend off its biggest creditor?

Under the proposed anti-counterfeit amendment, first-time offenders can receive a $5 million fine and 20 years prison for individuals, or $15 million for corporations; a penalty comparable to that of trafficking cocaine. While the amendment explicitly defines “counterfeit” to include refurbished parts represented as new, the wording is regrettably vague on whether you must be willfully trafficking such goods to also be liable for such a stiff penalty.

If you took a dirty but legitimately minted coin and washed it so that it looked mint condition and then sold it to a collector as mint quality, nobody would accuse you of counterfeiting. Yet, this amendment puts a 20 year, $5 million penalty on not only the act of counterfeiting chips destined for military use, but potentially the unwitting distribution of such chips that you putatively bought as new but couldn’t tell yourself if they were refurbished. Unfortunately, in many cases an electronic part can be used for years with no sign of external wear.

The amendment also has a provision to create an “inspection program”:

(b) Inspection of Imported Electronic Parts —

(1) … the Secretary of Homeland Security shall establish a program of enhanced inspection by U.S. Customs and Border patrol of electronic parts imported from any country that has been determined by the Secretary of Defense to have been a significant source of counterfeit electronic parts …

It’s one thing to inspect fruits and vegetables as they enter the country for pests and other problems; but it is misguided to require Customs officers to become experts in detecting fakes, and/or to burden vendors with the onus of determining whether parts are authentic, particularly with such high penalties involved and the relative ease that forgers can create high-quality counterfeit parts.

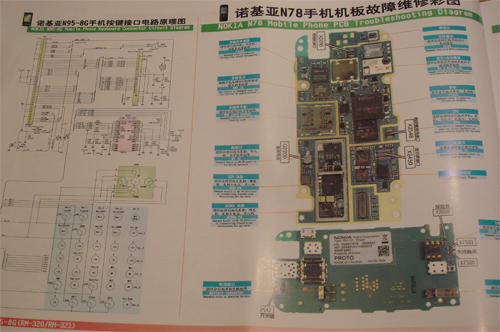

To better understand the magnitude of the counterfeiting problem, it’s helpful to know fakes are made. The fakes I’ve seen fall into the following broad categories:

1) Trivial external mimicry. Typically these are empty plastic packages with authentic-looking topmarks, or remarked parts that share only physical traits with the authentic parts (for example, a TTL logic chip in an SO-20 case remarked as an expensive microcontroller that uses the same SO-20 case). I consider this technique trivial because it is so easy to detect during factory test; in the worst case you are sold a thin mixture of authentic and conterfeit parts so that testing just one part out of a tube or reel isn’t good enough. However, in all cases the problem is discovered before the product ships so long as the product overall is thoroughly tested.

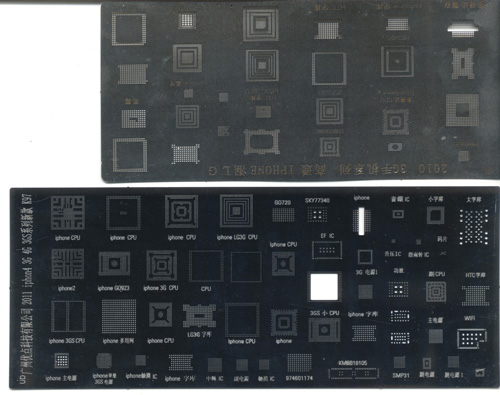

2) Refurbished parts. These are authentic parts recovered from e-waste that have been desoldered and reprocessed to appear as new. These are very difficult to spot since the chip is in fact authentic, and a skilled refurbisher can create stunningly authentic-looking results that can only be discriminated with the use of electronic micsoscopes and elemental/isotopic analysis. I also include in this category parts that are new only the sense they have never been soldered onto a board, but were stored improperly (for example, in a humid environment) and should be scrapped, but were subsequently reconditioned and sold like new.

3) Rebinned parts. These are parts that were authentic, and perhaps have never been used (so can be classified as “new”), but have their markings changed to reflect a higher specification of an identical function. A classic example is grinding and remarking CPUs with a higher speed grade, or more trivially parts that contain lead marked as RoHS-compliant. However, it can get as sophisticated as vendors reverse engineering and reprogramming the fuse codes inside the chip so that the chip’s electronic records match the faked markings on top; or vendors have been known to do deep hacks on Flash drive firmware so that a small memory can appear to a host OS as a much larger memory, going so far as to “loop” memory so that writes beyond the capacity of the device appear to succeed.

4) Ghost-shift parts. These are parts that are created on the exact same fabrication facility as authentic parts, but run by employees without authorization of the manufacturer and never logged on the books. Often times they are assigned a lot code identical to a legitimate run, but certain testing steps are skipped. These fakes can be extremely hard to detect. It’s like an employee in a mint striking extra coins after-hours.

5) Factory scrap. Factory rejects and pilot runs can be recovered from the scrap heap for a small bribe, and given authentic markings and resold as new. In order to avoid detection, workers often replace the salvaged scrap with physically identical dummy packages, thus foiling attempts to audit the scrap trail.

6) Second-sourcing gone bad. Second-sourcing is a standard industry practice where competitors create pin-compatible replacements for popular products in order to create price competition and strengthen the supply chain against events like natural disasters. The practice goes bad when inferior parts are re-marked with the logos of premium brands. High-value but functionally simple discrete analog chips such as power regulators are particularly vulnerable to this problem. Premium US brands can command a 10x markup over Asian brands, as “drop-in replacement” Asian-brand parts are notorious for spotty quality, cut corners and poor parametric performance. However, there is a lot of money to be made buying blanks from the second source fab and remarking them with authentic-looking top marks of premium US brands. In some cases there are no inexpensive or fast tests to detect these fakes, short of decapsulating the chip and comparing mask patterns and cross-sections.

In the case of the US Military, they have a unique problem where they are one of the biggest and wealthiest buyers of really old parts. Military designs have shelf lives of decades, but parts have production cycles of only years. It’s like asking someone to build a NeXT Cube motherboard today using only certifiably new parts; no secondhand or refurbished parts allowed. I don’t think it’s possible.

The impossibility of this situation may force military contractors to be complicit in the consumption of counterfeit parts. For example, the fake parts in the P-8 Poseidon were “badly refurbished”. A poor refurbishing job is probably detectable with a simple visual inspection, so even though people are quick to point fingers at China, maybe part of the problem is that the contractor was lax in checking incoming stock — or perhaps looking the other way, because if these are the last parts of its kind in the world, what else can they do?

Another part of the senate hearings revealed that L3 bought counterfeit video memory chips destined for C-27J aircraft from Global IC Trading Group. Well … duh. Global IC ain’t Digikey … they specialize in trading excess, overruns and secondhand goods. The prices are often good, but I only go to them if I’m really in a bind, and I’m willing to accept odd lots to get production moving at any cost. L3’s big enough to have a professional sourcing group aware of that, and thus exercise extreme caution when buying from such vendors.

My guess is that the stocks of any distributor in the secondhand electronics business are already flooded with undetected counterfeits. Remember, only the bad fakes are ever caught, and chip packaging was not designed with anti-counterfeiting measures in mind. While all gray market parts are suspect, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Gray markets play an essential role in the electronics ecosystem; using them is a calculated but sometimes unavoidable risk.

While the situation is clearly a mess now, some simple measures going forward could help fix things for the future. One could involve embedding anti-counterfeit measures in chips approved for military use. For chips larger than 1cm, a unique 2-D barcode can be applied with laser markings. The equipment to do such laser-marking is relatively commonplace today in chip packaging facilities. The efficacy of such techniques has been proven in biotech, where systems such as Matrix 2D are deployed to track disposable sample tubes in biology labs. Despite a tiny footprint, the codes are backed with a guarantee of 100% uniqueness. Another potential solution is to mix a UV dye into the component’s epoxy that changes fluorescence properties upon exposure to reflow temperatures. If the dye is distributed through the plastic body of the case, the change will be impossible to remove with grinding alone.

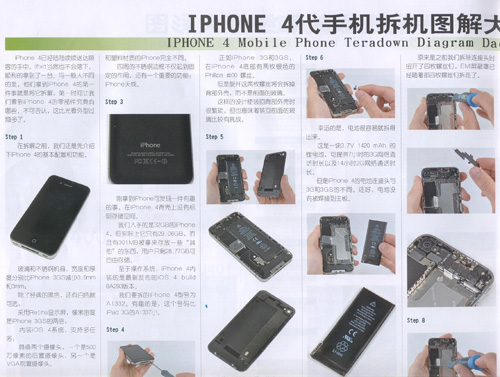

A second partial measure could be to manage e-waste better. E-waste is harvested in bulk for used parts. One can purchase crudely desoldered MSM7000-series chips (the brains of many Android smartphones) by the pound, at around ten cents for a chip. These chips are then cleaned up, reballed and sometimes remarked, put into tapes and reels and sold as brand new, commanding over a 10x markup. Thus, a single batch of chips can net thousands of dollars, making it a compelling source of income for skilled labor that would otherwise work in a factory for $200 per month.

If we stopped shipping our e-waste overseas for disposal, or at least ground up the parts before shipping them over, then the feedstock for such markets would be reduced. It could also create jobs domestically for processing the e-waste, which by the way is a source of gold comparable to the richest gold ore. On the other hand, I’m of the opinion that in the big picture this sort of component-level recycling is actually quite good for the environment and the human ecosystem. Upon disposal, most electronics still have years of serviceable life in them, and there is a hungry market for technology in emerging economies that cannot be met with new parts purchased on the primary market.

A final option could be to establish a strategic reserve of parts. A production run of military planes is limited to perhaps hundreds of units, and so I imagine the lifetime demand of a part including replacements is limited to tens of thousands of units. I can fit ten thousand chips in the volume of a large shoebox; at least physically, it’s not an unmanageable proposition. These are small volumes compared to consumer electronics volumes. I imagine that purchasing a reserve of raw replacement components for critical avionics systems would only add a fraction of a percent to the cost of an airplane, and could even lead to long term cost savings as manufacturers can achieve greater scale efficiency if they run one large batch all at once. This could be a foolproof method to ensure supply trustability for critical military hardware.