I think turning everyday gadgets into bombs is a bad idea. However, recent news coverage has been framing the weaponization of pagers and radios in the Middle East as something we do not need to concern ourselves with because “we” are safe.

I respectfully disagree. Our militaries wear uniforms, and our weapons of war are clearly marked as such because our societies operate on trust. As long as we don’t see uniformed soldiers marching through our streets, we can assume that the front lines of armed conflict are far from home. When enemies violate that trust, we call it terrorism, because we no longer feel safe around everyday people and objects.

The reason we don’t see exploding battery attacks more often is not because it’s technically hard, it’s because the erosion of public trust in everyday things isn’t worth it. The current discourse around the potential reach of such explosive devices is clouded by the assumption that it’s technically difficult to implement and thus unlikely to find its way to our front door.

That assumption is wrong. It is both surprisingly easy to do, and could be nearly impossible to detect. After I read about the attack, it took half an hour to combine fairly common supply chain knowledge with Wikipedia queries to propose the mechanism detailed below.

Why It’s Not Hard

Lithium pouch batteries are ubiquitous. They are produced in enormous volumes by countless factories around the world. Small laboratories in universities regularly build them in efforts to improve their capacity and longevity. One can purchase all the tools to produce batteries in R&D quantities for a surprisingly small amount of capital, on the order of $50,000. This is a good thing: more people researching batteries means more ideas to make our gadgets last longer, while getting us closer to our green energy objectives even faster.

Above is a screenshot I took today of search results on Alibaba for “pouch cell production line”.

The process to build such batteries is well understood and documented. Here is an excerpt from one vendor’s site promising to sell the equipment to build batteries in limited quantities (tens-to-hundreds per batch) for as little as $15,000:

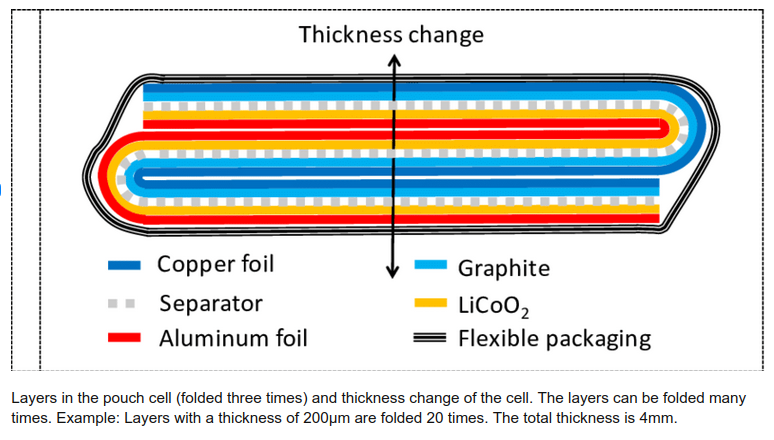

Pouch cells are made by laying cathode and anode foils between a polymer separator that is folded many times:

Above from “High-resolution Interferometric Measurement of Thickness Change on a Lithium-Ion Pouch Battery” by Gunther Bohn, DOI:10.1088/1755-1315/281/1/012030, CC BY 3.0

The stacking process automated, where a machine takes alternating layers of cathode and anode material (shown as bare copper in the demo below) and wraps them in separator material:

There’s numerous videos on Youtube showing how this is done, here’s a couple of videos to get you started if you are curious.

After stacking, the assembly is laminated into an aluminum foil pouch, which is then trimmed and marked into the final lithium pouch format:

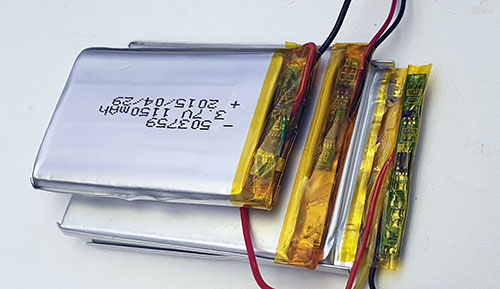

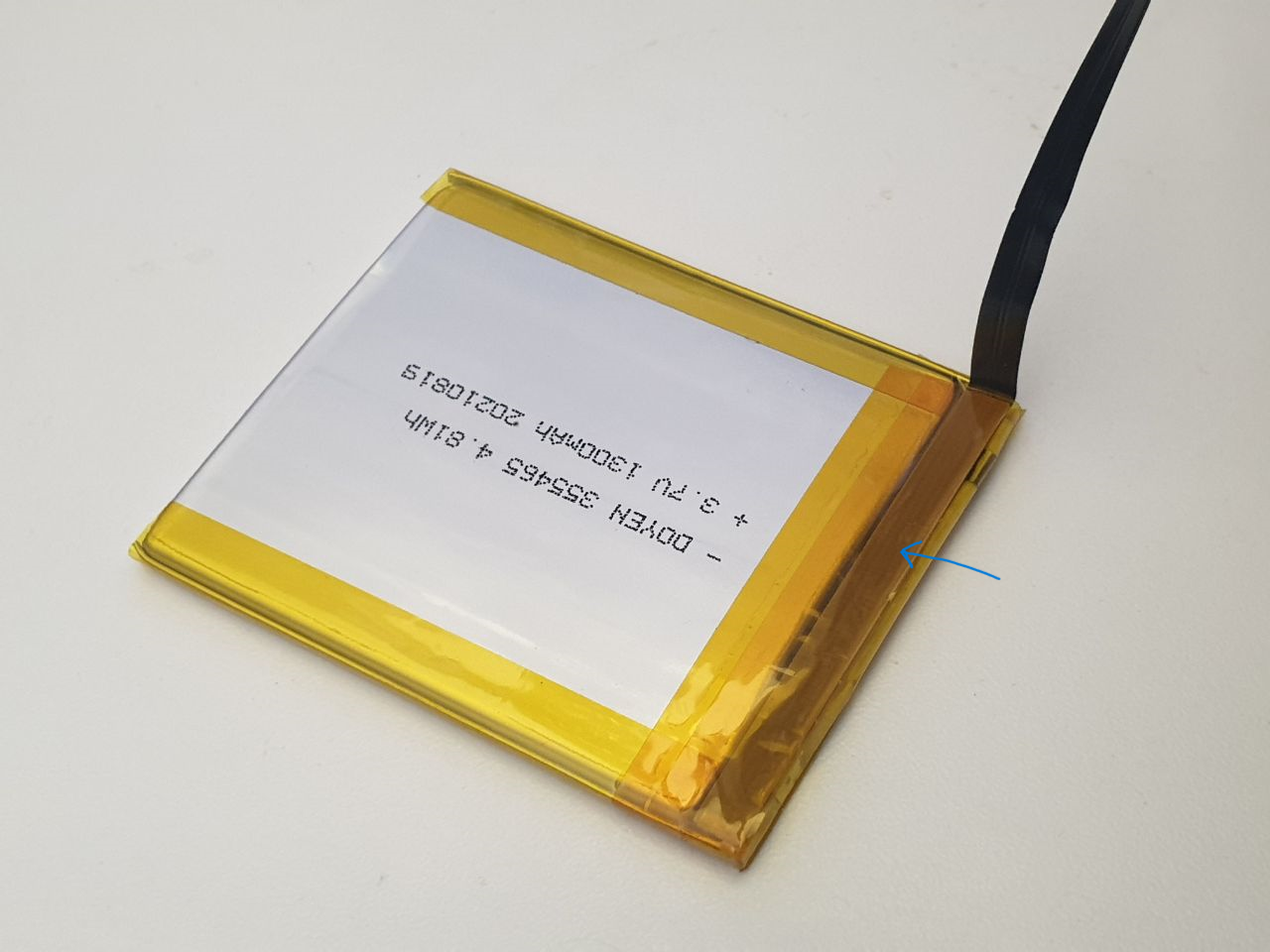

Above is a cell I had custom-fabricated for a product I make, the Precursor. It probably has about 10-15 layers inside, and it costs a few thousand dollars and a few weeks to get a thousand of these made. Point is, making custom pouch batteries isn’t rocket science – there’s a whole bunch of people who know how to do it, and a whole industry behind it.

Reports indicate the explosive payload in the cells is made of PETN. I can’t comment on how credible this is, but let’s assume for now that it’s accurate. I’m not an expert in organic chemistry or explosives, but a read-through the Wikipedia page indicates that it’s a fairly stable molecule, and it can be incorporated with plasticizers to create plastic explosives. Presumably, it can be mixed with binders to create a screen-printed sheet, and passivated if needed to make it electrically insulating. The pattern of the screen printing may be constructed to additionally create a shaped-charge effect, increasing the “bang for the buck” by concentrating the shock wave in an area, effectively turning the case around the device into a small fragmentation grenade.

Such a sheet could be inserted into the battery fold-and-stack process, after the first fold is made (or, with some effort, perhaps PETN could be incorporated into the spacer polymer itself – but let’s assume for now it’s just a drop-in sheet, which is easy to execute and likely effective). This would have the effect of making one of the cathode/anode pairs inactive, reducing the battery capacity, but only by a small amount: only one layer out of at least 10 layers is affected, thus reducing capacity by 10% or less. This may be well within the manufacturing tolerance of an inexpensive battery pack; alternatively, the cell could have an extra layer added to it to compensate for the capacity loss, with a very minor increase in the pack height (0.2mm or so, about the thickness of a sheet of paper – within the “swelling tolerance” of a battery pack).

Why It Could Be Hard to Detect

Once folded into the core of the battery, it is sealed in an aluminum pouch. If the manufacturing process carefully isolates the folding line from the laminating line, and/or rinses the outside of the pouch with acetone to dissolve away any PETN residue prior to marking, no explosive residue can escape the pouch, thus defeating swabs that look for chemical residue. It may also well evade methods such as X-Ray fluorescence (because the elements that compose the battery, separator and PETN are too similar and too light to be detected), and through-case methods like SORS (Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy) would likely be defeated by the multi-layer copper laminate structure of the battery itself blocking light from probing the inner layers.

Thus, I would posit that a lithium battery constructed with a PETN layer inside is largely undetectable: no visual inspection can see it, and no surface analytical method can detect it. I don’t know off-hand of a low-cost, high-throughput X-ray method that could detect it. A high-end CT machine could pick out the PETN layer, but it’d cost around a million dollars for one machine and scan times are around a half hour – not practical for i.e. airport security or high throughput customs screening. Electrical tests of capacity and impedance through electromechanical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) may struggle to differentiate a tampered battery from good batteries, especially if the battery was specifically engineered to fool such tests. An ultrasound test might be able to detect an extra layer, but it would require the battery to placed in intimate contact with an ultrasound scanner for screening. I also think that that PETN could be incorporated into the spacer polymer film itself, which would defeat even CT scanners (but may leave a detectable EIS fingerprint). Then again, this is just what I’m coming up with stream-of-consciousness: presumably an adversary with a staff of engineers and months of time could figure out numerous methods more clever than what I came up with shooting from the hip.

Detonating the PETN is a bit more tricky; without a detonator, PETN may conflagrate (burn fast), instead of detonating (and creating the much more damaging shock wave). However, the Wikipedia page notes that an electric spark with an energy in the range of 10-60 mJ is sufficient to initiate detonation.

Based on an available descriptions of the devices “getting hot” prior to detonation, one might suppose that detonation is initiated by a trigger-circuit shorting out the battery pack, causing the internal polymer spacers to melt, and eventually the cathode/anode pairs coming into contact, creating a spark. Such a spark may furthermore be guaranteed across the PETN sheet by introducing a small defect – such as a slight dimple – in the surrounding cathode/anode layers. Once the pack gets to the melting point of the spacers, the dimpled region is likely to connect, leading to a spark that then detonates the PETN layer sandwiched in between the cathode and anode layers.

But where do you hide this trigger-circuit?

It turns out that almost every lithium polymer pack has a small circuit board embedded in it called the PCM or “protection circuit module”. It contains a microcontroller, often in a “TSSOP-8” package, and at least one or more large transistors capable of handling the current capacity of the battery.

I’ve noted where the protection circuit is on my custom battery pack with a blue arrow. No electronics are visible because the circuit is folded over to protect the electronics from damage.

And above is a selection of three pouch cells that happen to have readily visible protection circuitry. The PCM is the thin green circuit board on the right hand side, covered in protective yellow tape. One take-away from this image is the diversity inherent in PCM modules: in fact, vendors may switch out PCM modules for functionally equivalent ones depending on component availability constraints.

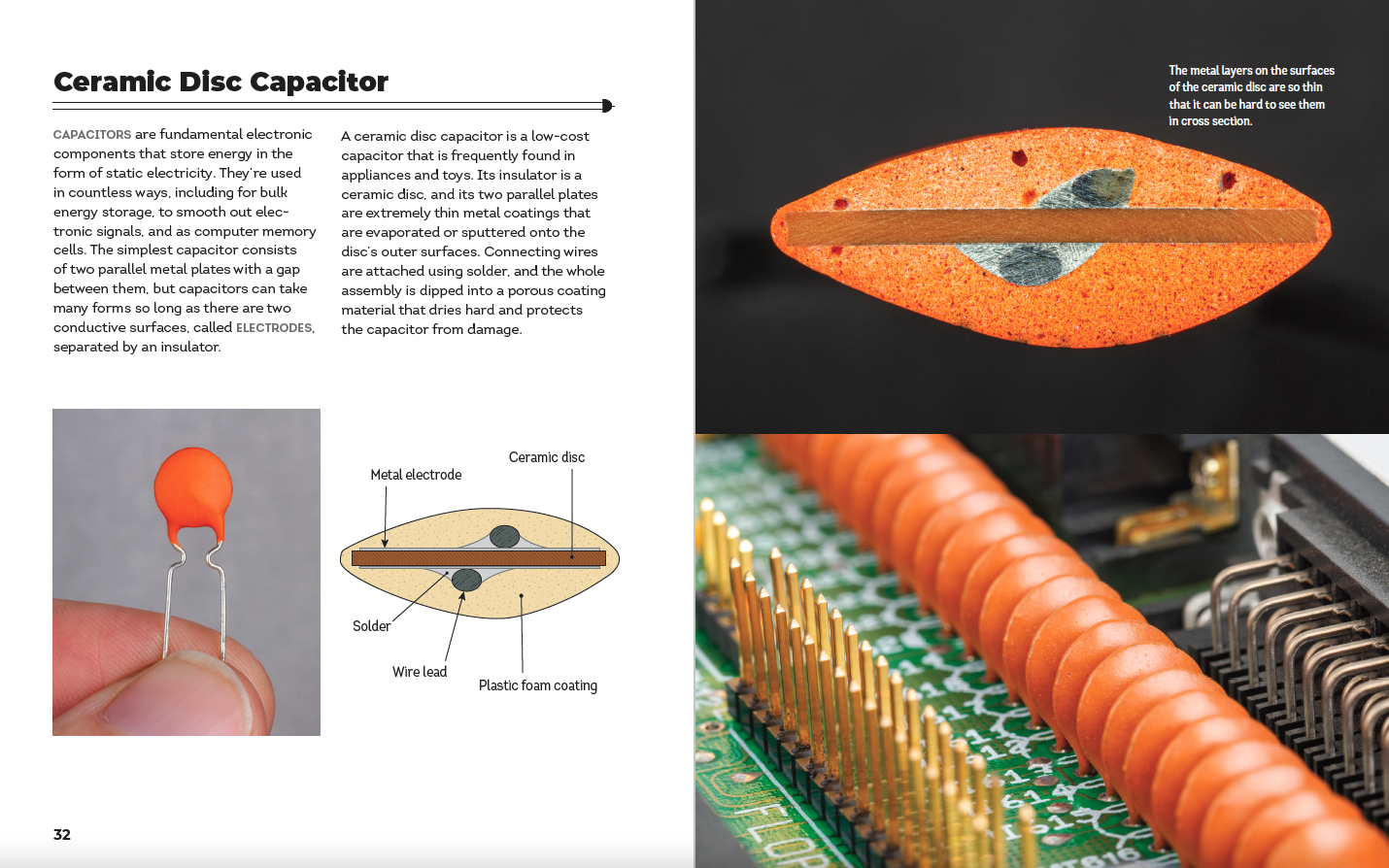

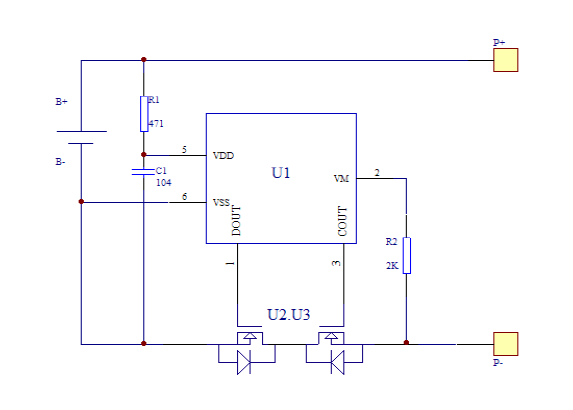

Normally, the protection circuit has a simple job: sample the current flow and voltage of the pack, and if these go outside of a pre-defined range, turn off the flow of current.

Above: Example of a protection circuit inside a pouch battery. U1 is the controller IC, while U2 and U3 are two separate transistors employed to block current flow in both directions. One of these transistors can be repurposed to short across the battery while still leaving one transistor for protection use (able to block current flow in one direction). Thus the cell is still partially protected despite having a trigger circuit, defeating attempts to detect a modified circuit by simply counting the number of components on the circuit board, or by doing a simple short-circuit or overvoltage test.

A small re-wiring of traces on the protection circuit board gives you a circuit that instead of protecting the battery from out-of range conditions, turns it into a detonator for the PETN layer. One of the transistors that is normally used to cut the flow of electricity is instead wired across the terminals of the battery, allowing for a selective short circuit that can lead to the melting of the spacer layers, ultimately leading to a spark between the dimpled anode/cathode layers and thus detonation of the PETN.

The trigger itself may come via a “third wire” that is typically present on battery packs: the NTC temperature sensor. Many packs contain a safety feature where a nominally 10k resistor is provided to ground that has a so-called “negative temperature coefficient”, i.e., a resistance that changes in a well-characterized fashion with respect to temperature. By measuring the resistance, an external controller can detect if the pack is overheating, and disconnect it to prevent further damage.

However, the NTC can also be used as a one-wire communication bus: the controller IC on the protection circuit can readily sample the voltage on the NTC wire. Normally, the NTC has some constant positive bias applied to it; but if the NTC is connected to ground in a unique pattern, that can serve as a coded trigger to detonate.

The entirety of such a circuit could conceivably be implemented using an off-the-shelf microcontroller, such as the Microchip/Atmel Attiny 85/V, a TSSOP-8 device that would look perfectly at-home on a battery protection PCB, yet contains an on-board oscillator and sufficient code space such that it could decode a trigger pattern.

If the battery charger is integrated into the main MCU – which it often is in highly cost-reduced products such as pagers and walkie-talkies – the trigger sequence can be delivered to the battery with no detectable modification to the target device. Every circuit trace and component would be where it’s supposed to be, and the MCU would be an authentic, stock MCU.

The only difference is in the code: in addition to mapping a GPIO to an analog input to sample the NTC, the firmware would be modified to convert the GPIO into an output at “trigger time” which would pull the NTC to ground in the correct sequence to trigger the battery to explode. Note that this kind of flexibility of pin function is quite typical for modern microcontrollers.

Technical Summary

Thus, one could conceivably create a supply chain attack to put exploding batteries into everyday devices that is undetectable: the main control board is entirely unmodified; only a firmware change is needed to incorporate the trigger. It would pass every visual and electrical inspection.

The only component that has to be swapped out is the lithium pouch battery, which itself can be constructed for an investment as small as $15,000 in equipment (of course you’d need a specialist to operate the equipment, but pouch cells are ubiquitous enough that it would not be surprising to find a line at any university doing green-energy research). The lithium pouch cell itself can be constructed with an explosive layer that I hypothesize would be undetectable to most common analytical methods, and the detonator trigger can be constructed so that it is visually and mostly electrically indistinguishable from the protection circuit module that would be included on a stock lithium pouch battery, using only common, off-the-shelf components. Of course, if the adversary has the budget to make a custom chip, they could make the entire protection circuit perfectly indistinguishable to most forms of non-destructive inspection.

How To Attack a Supply Chain

Insofar as how one can get such cells and firmware updates into the supply chain – see any of my prior talks about the vulnerability of hardware supply chains to attack. For example: this talk which I gave in Israel in 2019 at the BlueHat event, outlining the numerous attack surfaces and porosity of modern hardware supply chains.

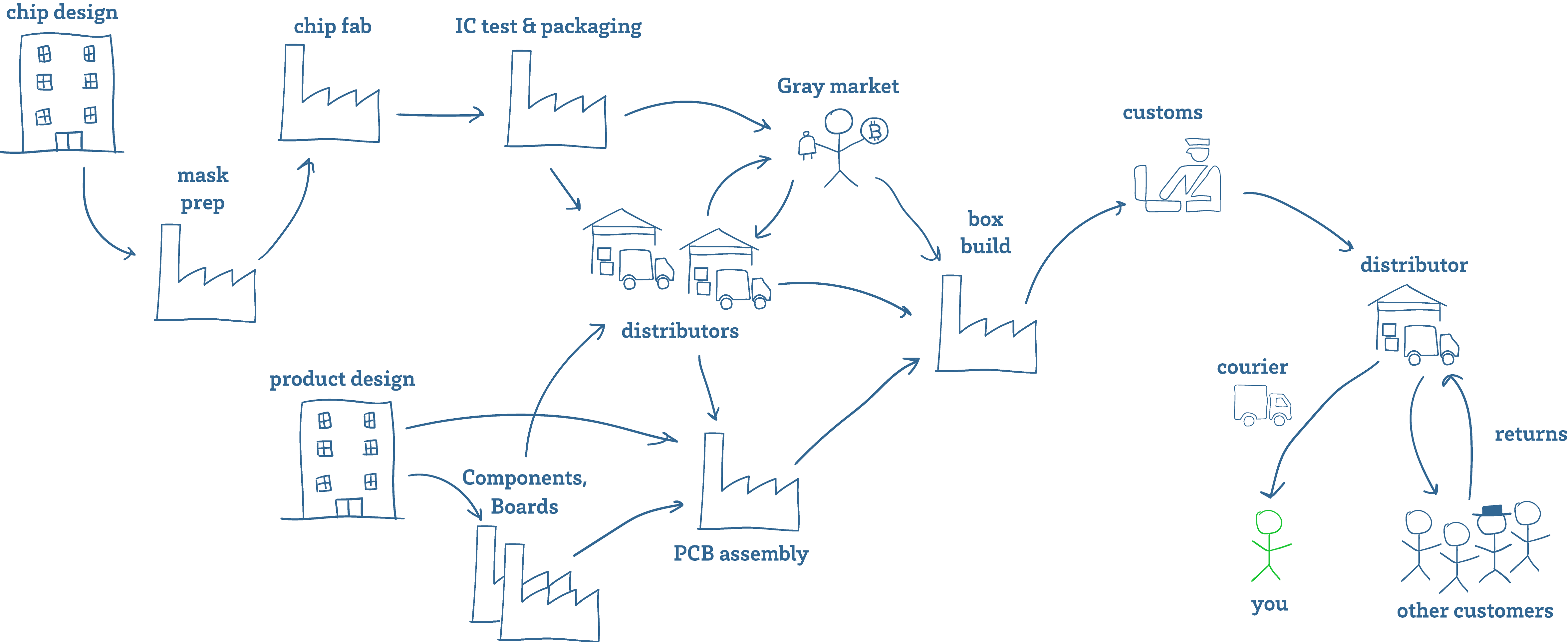

Above is a cartoon sketch of a supply chain. Getting fake components into the supply chain is easier than you might think. As a manufacturer of hardware, I have to deal with fake components all the time. This is especially true for batteries – most popular consumer electronic devices already have a healthy gray market for replacement batteries. These are batteries that look the same as OEM batteries and fetch an OEM price, but are made with sub-par components.

Aside from taking advantage of gray and secondary markets, there are multiple opportunities along the route from the factory to you to tamper with goods – from the customs inspector, to the courier.

But you don’t even have to go so far as offering anyone a bribe or being a state-level agency to get tampered batteries into a supply chain. Anyone can buy a bunch of items from Amazon, swap out the batteries, restore the packaging and seals, and return the goods to the warehouse (and yes, there is already a whole industry devoted to copying packaging and security seals for the purpose of warranty fraud). The perpetrator will be long-gone by the time the device is resold. Depending on the objective of the campaign, no further targeting may be necessary – just reports of dozens of devices simultaneously detonating in your home town may be sufficient to achieve a nefarious objective.

Note that such a “reverse-logistics injection attack” works even if you on-shore all your factories, and tariff the hell out of everyone else. Any “tourist” with a suitcase is all it takes.

Pandora’s Box is Open

Not all things that could exist should exist, and some ideas are better left unimplemented. Technology alone has no ethics: the difference between a patch and an exploit is the method in which a technology is disclosed. Exploding batteries have probably been conceived of and tested by spy agencies around the world, but never deployed en masse because while it may achieve a tactical win, it is too easy for weaker adversaries to copy the idea and justify its re-deployment in an asymmetric and devastating retaliation.

However, now that I’ve seen it executed, I am left with the terrifying realization that not only is it feasible, it’s relatively easy for any modestly-funded entity to implement. Not just our allies can do this – a wide cast of adversaries have this capability in their reach, from nation-states to cartels and gangs, to shady copycat battery factories just looking for a big payday (if chemical suppliers can moonlight in illicit drugs, what stops battery factories from dealing in bespoke munitions?). Bottom line is: we should approach the public policy debate around this assuming that someday, we could be victims of exploding batteries, too. Turning everyday objects into fragmentation grenades should be a crime, as it blurs the line between civilian and military technologies.

I fear that if we do not universally and swiftly condemn the practice of turning everyday gadgets into bombs, we risk legitimizing a military technology that can literally bring the front line of every conflict into your pocket, purse or home.