A few editors have approached me about writing a book on manufacturing, but that’s a bit like asking an architect to take a photo of a building that’s still on the drawing board. The story is still unfolding; I feel as if I’m still fumbling in the dark trying to find my glasses. So, when Maker Media approached me to write a chapter for their upcoming “Maker Pro” book, I thought perhaps this was a good opportunity to make a small and manageable contribution.

The Maker Pro book is a compendium of vignettes written by 17 Makers, and you can pre-order the Maker Pro book at Amazon now.

Maker Media was kind enough to accommodate my request to license my contribution using CC BY-SA-3.0. As a result, I can share my chapter with you here. I titled it the “Soylent Supply Chain” and it’s about the importance of people and relationships when making physical goods.

Soylent Supply Chain

The convenience of modern retail and ecommerce belies the complexity of supply chains. With a few swipes on a tablet, consumers can purchase almost any household item and have it delivered the next day, without facing another human. Slick marketing videos of robots picking and packing components and CNCs milling components with robotic precision create the impression that everything behind the retail front is also just as easy as a few search queries, or a few well-worded emails. This notion is reinforced for engineers who primarily work in the domain of code; system engineers can download and build their universe from source–the FreeBSD system even implements a command known as ‘make buildworld’, which does exactly that.

The fiction of a highly automated world moving and manipulating atoms into products is pervasive. When introducing hardware startups to supply chains in practice, almost all of them remark on how much manual labor goes into supply chains. Only the very highest volume products and select portions of the supply chain are well-automated, a reality which causes many to ask me, “Can’t we do something to relieve all these laborers from such menial duty?” As menial as these duties may seem, in reality, the simplest tasks for humans are incredibly challenging for a robot. Any child can dig into a mixed box of toys and pick out a red 2×1 Lego brick, but to date, no robot exists that can perform this task as quickly or as flexibly as a human. For example, the KIVA Systems mobile-robotic fulfillment system for warehouse automation still requires humans to pick items out of self-moving shelves, and FANUC pick/pack/pal robots can deal with arbitrarily oriented goods, but only when they are homogeneous and laid out flat. The challenge of reaching into a box of random parts and producing the correct one, while being programmed via a simple voice command, is a topic of cutting-edge research.

bunnie working with a factory team. Photo credit: Andrew Huang.

The inverse of the situation is also true. A new hardware product that can be readily produced through fully automated mechanisms is, by definition, less novel than something which relies on processes not already in the canon of fully automated production processes. A laser-printed sheet will always seem more pedestrian than a piece of offset-printed, debossed, and metal-film transferred card stock. The mechanical engineering details of hardware are particularly refractory when it comes to automation; even tasks as simple as specifying colors still rely on the use of printed Pantone registries, not to mention specifying subtleties such as textures, surface finishes, and the hand-feel of buttons and knobs. Of course, any product’s production can be highly automated, but it requires a huge investment and thus must ship in volumes of millions per month to amortize the R&D cost of creating the automated assembly line.

Thus, supply chains are often made less of machines, and more of people. Because humans are an essential part of a supply chain, hardware makers looking to do something new and interesting oftentimes find that the biggest roadblock to their success isn’t money, machines, or material: it’s finding the right partners and people to implement their vision. Despite the advent of the Internet and robots, the supply chain experience is much farther away from Amazon.com or Target than most people would assume; it’s much closer to an open-air bazaar with thousands of vendors and no fixed prices, and in such situations getting the best price or quality for an item means building strong personal relationships with a network of vendors. When I first started out in hardware, I was ill-equipped to operate in the open-market paradigm. I grew up in a sheltered part of Midwest America, and I had always shopped at stores that had labeled prices. I was unfamiliar with bargaining. So, going to the electronics markets in Shenzhen was not only a learning experience for me technically, it also taught me a lot about negotiation and dealing with culturally different vendors. While it’s true that a lot of the goods in the market are rubbish, it’s much better to fail and learn on negotiations over a bag of LEDs for a hobby project, rather than to fail and learn on negotiations on contracts for manufacturing a core product.

One of bunnie’s projects is Novena, an open source laptop. Photo credit: Crowd Supply.

This point is often lost upon hardware startups. Very often I’m asked if it’s really necessary to go to Asia–why not just operate out of the US? Aren’t emails and conference calls good enough, or worst case, “can we hire an agent” who manages everything for us? I guess this is possible, but would you hire an agent to shop for dinner or buy clothes for you? The acquisition of material goods from markets is more than a matter of picking items from the shelf and putting them in a basket, even in developed countries with orderly markets and consumer protection laws. Judgment is required at all stages — when buying milk, perhaps you would sort through the bottles to pick the one with greatest shelf life, whereas an agent would simply grab the first bottle in sight. When buying clothes, you’ll check for fit, loose strings, and also observe other styles, trends, and discounted merchandise available on the shelf to optimize the value of your purchase. An agent operating on specific instructions will at best get you exactly what you want, but you’ll miss out better deals simply because you don’t know about them. At the end of the day, the freshness of milk or the fashion and fit of your clothes are minor details, but when producing at scale even the smallest detail is multiplied thousands, if not millions of times over.

More significant than the loss of operational intelligence, is the loss of a personal relationship with your supply chain when you surrender management to an agent or manage via emails and conference calls alone. To some extent, working with a factory is like being a houseguest. If you clean up after yourself, offer to help with the dishes, and fix things that are broken, you’ll always be welcome and receive better service the next time you stay. If you can get beyond the superficial rituals of politeness and create a deep and mutually beneficial relationship with your factory, the value to your business goes beyond money–intangibles such as punctuality, quality, and service are priceless.

I like to tell hardware startups that if the only value you can bring to a factory is money, you’re basically worthless to them–and even if you’re flush with cash from a round of financing, the factory knows as well as you do that your cash pool is finite. I’ve had folks in startups complain to me that in their previous experience at say, Apple, they would get a certain level of service, so how come we can’t get the same? The difference is that Apple has a hundred billion dollars in cash, and can pay for five-star service; their bank balance and solid sales revenue is all the top-tier contract manufacturers need to see in order to engage.

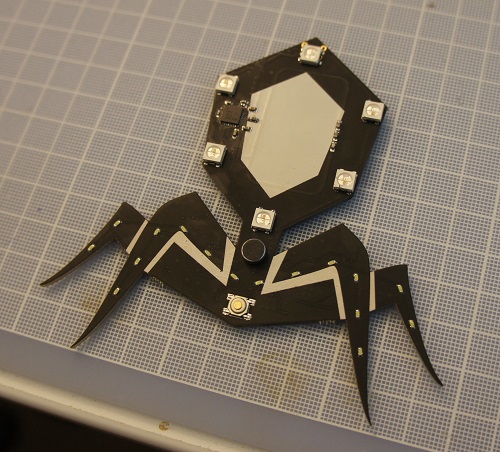

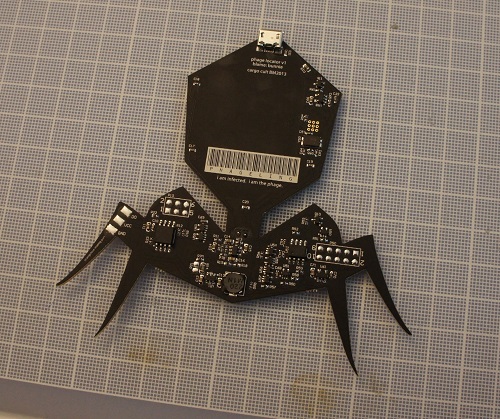

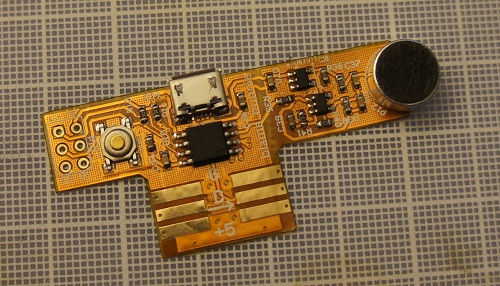

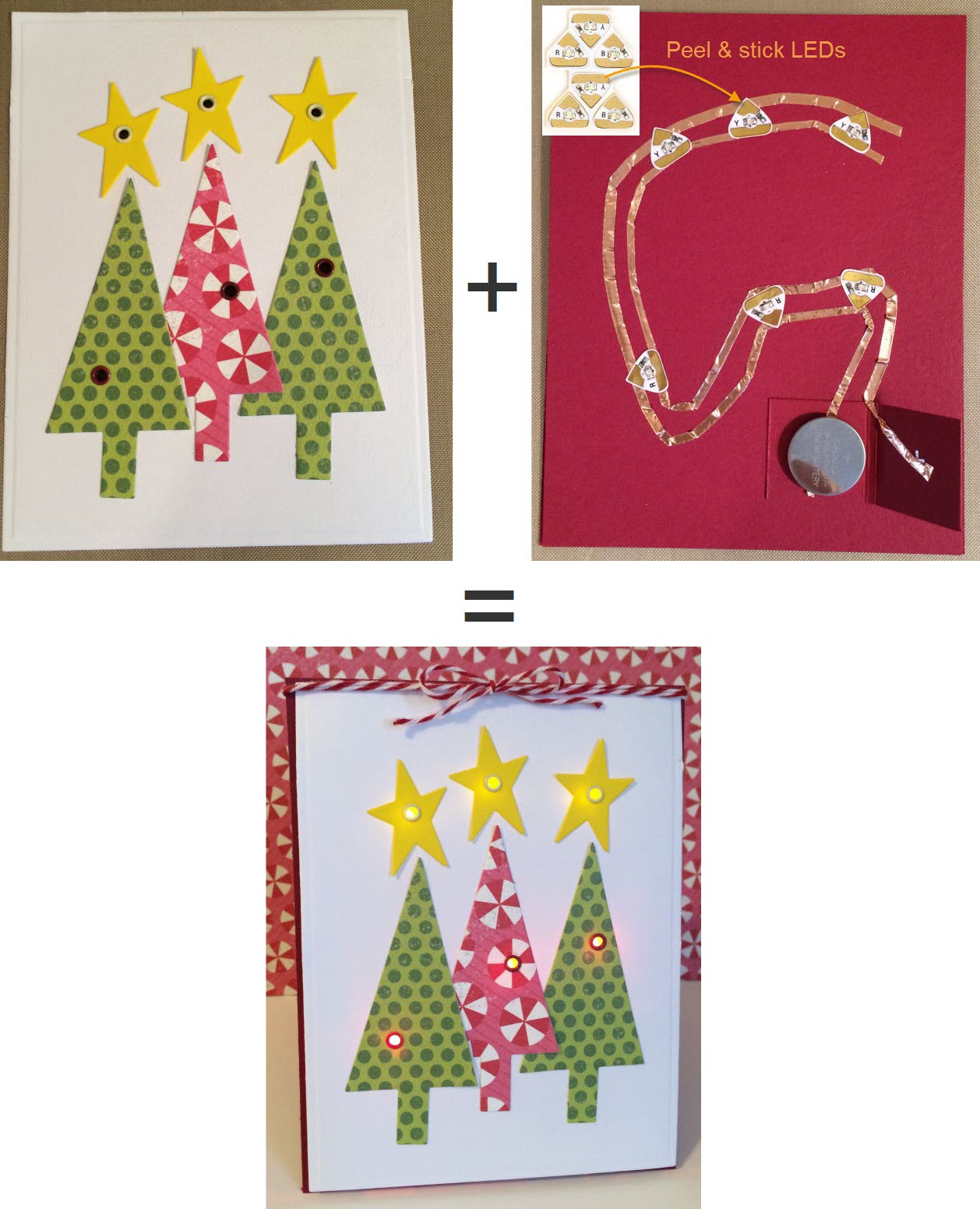

Circuit Stickers, adhesive-backed electronic components, is another of bunnie’s projects. Photo credit: Andrew “bunnie” Huang.

On the other hand, hardware startups have to hitchhike and couch-surf their way to success. As a result, it’s strongly recommended to find ways other than money to bring value to your partners, even if it’s as simple as a pleasant demeanor and an earnest smile. The same is true in any service industry, such as dining. If you can afford to eat at a three-star Michelin restaurant, you’ll always have fairy godmother service, but you’ll also have a $1,000 tab at the end of the meal. The local greasy spoon may only set you back ten bucks, but in order to get good service it helps to treat the wait staff respectfully, perhaps come at off-peak hours, and leave a good tip. Over time, the wait staff will come to recognize you and give you priority service.

At the end of the day, a supply chain is made out of people, and people aren’t always rational and sometimes make mistakes. However, people can also be inspired and taught, and will work tirelessly to achieve the goals and dreams they earnestly believe in: happiness is more than money, and happiness is something that everyone wants. For management, it’s important to sell your product to the factory, to get them to believe in your vision. For engineers, it’s important to value their effort and respect their skills; I’ve solved more difficult problems through camaraderie over beers than through PowerPoint in conference rooms. For rank-and-file workers, we try our best to design the product to minimize tedious steps, and we spend a substantial amount of effort making the tools we provide them for production and testing to be fun and engaging. Where we can’t do this, we add visual and audio cues that allow the worker to safely zone out while long and boring processes run. The secret to running an efficient hardware supply chain on a budget isn’t just knowing the cost of everything and issuing punctual and precise commands, but also understanding the people behind it and effectively reading their personalities, rewarding them with the incentives they actually desire, and guiding them to improve when they make mistakes. Your supply chain isn’t just a vendor; they are an extension of your own company.

Overall, I’ve found that 99% of the people I encounter in my supply chain are fundamentally good at heart, and have an earnest desire to do the right thing; most problems are not a result of malice, but rather incompetence, miscommunication, or cultural misalignment. Very significantly, people often live up to the expectations you place on them. If you expect them to be bad actors, even if they don’t start out that way, they have no incentive to be good if they are already paying the price of being bad — might as well commit the crime if you know you’ve been automatically judged as guilty with no recourse for innocence. Likewise, if you expect people to be good, oftentimes they will rise up and perform better simply because they don’t want to disappoint you, or more importantly, themselves. There is the 1% who are truly bad actors, and by nature they try to position themselves at the most inconvenient road blocks to your progress, but it’s important to remember that not everyone is out to get you. If you can gather a syndicate of friends large enough, even the bad actors can only do so much to harm you, because bad actors still rely upon the help of others to achieve their ends. When things go wrong your first instinct should not be “they’re screwing me, how do I screw them more,” but should be “how can we work together to improve the situation?”

In the end, building hardware is a fundamentally social exercise. Generally, most interesting and unique processes aren’t automated, and as such, you have to work with other people to develop bespoke processes and products. Furthermore, physical things are inevitably owned or operated upon by other people, and understanding how to motivate and compel them will make a difference in not only your bottom line, but also in your schedule, quality, and service level. Until we can all have Tony Stark’s JARVIS robot to intelligently and automatically handle hardware fabrication, any person contemplating manufacturing hardware at scale needs to understand not only circuits and mechanics, but also how to inspire and effectively command a network of suppliers and laborers.

After all, “it’s people — supply chains are made out of people!”