The microSD ware for January 2010 was not an incidental post. It is actually snapshot of a much longer forensic investigation to find the ground truth behind some irregular Kingston

ware for January 2010 was not an incidental post. It is actually snapshot of a much longer forensic investigation to find the ground truth behind some irregular Kingston memory cards.

memory cards.

It all started back in December of 2009, when chumby was in the midst of production for the chumby One. A call came in from the floor noting that SMT yield had dropped dramatically on one lot, so I drove over to the building to have a look (this is the advantage of being in China during production — you can fix problems like this within the hour, before they become really serious issues). After poking and prodding a bit, I realized that all the units failing had Kingston microSD cards from a particular lot code. I had the factory pull the entire lot of microSD cards from the line and rework all the units that had these cards loaded. Sure enough, after subtracting these cards from the line, yield was back to normal again.

was in the midst of production for the chumby One. A call came in from the floor noting that SMT yield had dropped dramatically on one lot, so I drove over to the building to have a look (this is the advantage of being in China during production — you can fix problems like this within the hour, before they become really serious issues). After poking and prodding a bit, I realized that all the units failing had Kingston microSD cards from a particular lot code. I had the factory pull the entire lot of microSD cards from the line and rework all the units that had these cards loaded. Sure enough, after subtracting these cards from the line, yield was back to normal again.

Normally, the story would end there; you’d RMA the material, get an exchange for the lot, and move on. Except there were a couple of problems. First, Kingston wouldn’t take the cards back because we had programmed them. Second, there was a lot of them — about a thousand all together, and chumby was already deeply back-ordered. Also, memory cards aren’t cheap; the spot price on this type of memory card is around $4-5, so it’s a few thousand dollars in scrap if we can’t get them exchanged … and neither chumby nor the CM is large enough to sneeze at a few kilobucks.

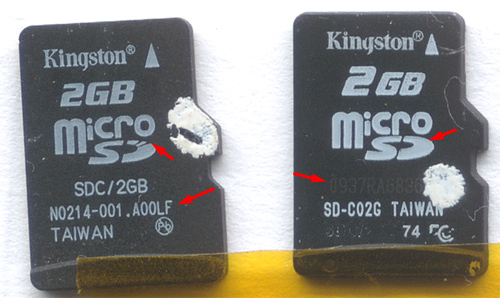

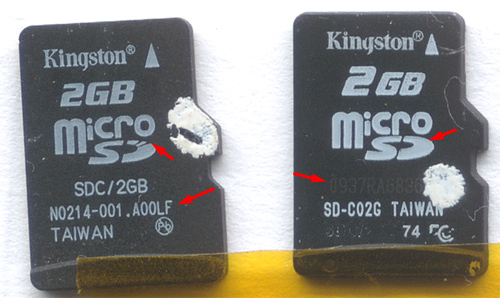

So I kicked into forensic mode. The first thing that raised my suspicions is the external markings on the irregular Kingston cards.

On the left is a sample of the irregular card. On the right is a sample of a normal card. I’ve put red arrows on the details that called the most attention to me at first.

The most blatantly strange issue is that the card on the left has its lot code silkscreened using the same stencil as the main logo. Silkscreening a lot code on isn’t that unusual, but typically the silk does not share the same stencil as the logo, so you’ll see some small variance in the coloration, font, or alignment of the lot code from the rest of the text. In fact, across the entire batch of irregular cards, they shared the exact same lot code (N0214-001.A00LF) (typically the lot code will vary every couple hundred cards at least). This is in contrast to the card on the right, which is laser-marked, and has a lot code that varied with every tray of 96 units.

The second strange issue, perhaps more subtle and perhaps not damning, is the irregularity in the “D” of the microSD logo. Typically, brand name vendors like Kingston would be very picky about the accuracy of their logos. The broken D is something found on SanDisk cards, but Kingston cards found in US retail almost universally use a solid D.

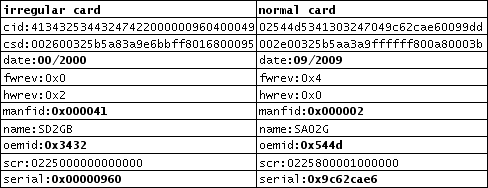

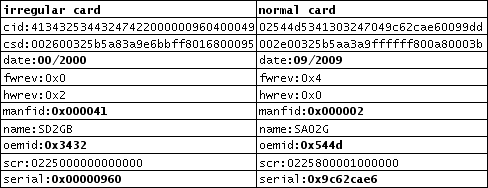

It turns out the weirdness in the external markings is just the start of it. When we read out the electronic card ID data on the two cards (available through /sys entries in linux), this is what we found:

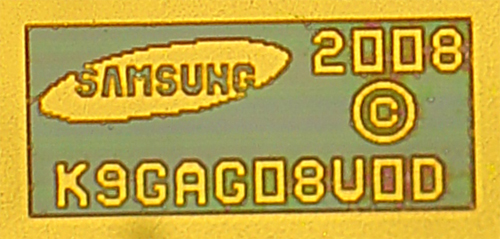

First, the date code on the irregular card is uninitialized. Dates are counted as the offset from 00/2000 in the CID field, so a value of 00/2000 means they didn’t bother to assign a date (for what it’s worth, in the year 2000, 2GB microSD cards also didn’t exist). Also, the serial number is very low — 0x960 is decimal 2,400. Other cards in the irregular batch also had similarly very low serial numbers, in the hundreds to thousands range. The chance of me “just happening” to get the very first microSD cards out of a factory is pretty remote. The serial number of the normal card, for example, is 0x9C62CAE6, or decimal 2,623,720,166 — a much more feasible serial number for a popular product like a microSD card. Very low serial numbers, like very low MAC ID addresses, are a hallmark of the “ghost shift”, i.e. the shift that happens very late at night when a rouge worker enters the factory and runs the production machine off the books. Significantly, ghost shifts are often run using marginal material that would normally be disposed of but were intercepted on the way to the grinder. As a result, the markings and characteristics of the material often look absolutely authentic, because the ghost material is a product of the same line as genuine material.

Furthermore, the manufacturer’s ID is 0x41 (ASCII ‘A’), which I don’t recognize (supposedly the SD group assigns all the MIDs but I don’t see a public list of them anywhere). The OEMID is also 0x3432, which is suspiciously ASCII ’42’ (one more than the hex value for the manufacturer ID). These hex/ascii confusions are possible signs that someone who didn’t appreciate the meaning of these fields was running a ghost shift making these cards.

Armed with this evidence, we confronted Kingston — both the distributor in China as well as the US sales rep. First, we wanted to know if these were real cards, and second, if they were real cards, why were the serialization codes irregular? After some time, the Kingston guys came back to us and swore these cards were authentic, not fakes, but at least they reversed their position on not offering an exchange on the cards — they took back the programmed cards and exchanged them for new ones, no further questions asked.

However, they never answered as to why their card ID numbers were irregular. While I know chumby is a small fry customer compared to the Nokias of the world, I think it’s still important that they answer basic questions about their quality control process even to the small fry. I had an issue once with an old version of a Quintic part being accidentally shipped to me, and once I could prove the issue to them, I received world-class customer service from Quintic, a full explanation, and an immediate and full exchange of the parts at their cost. That was exemplary service, and I commend and strongly recommend Quintic for it. Kingston, on the other hand, did not set an example to follow.

Normally, at this point, I would simply disqualify Kingston as a vendor, but I’m more persistent than that. It’s disconcerting that a high-profile, established brand would stand behind such irregular components. Who is to say SanDisk or Samsung wouldn’t do the same? Price erosion has been brutal on all the FLASH vendors, and as small fry I might be repeatedly taken advantage of as a sink for marginal material to improve the FLASH vendor’s bottom lines. Given the relatively high cost of these components, I needed to develop some simple guidelines for IQC (incoming quality control) inspection to accept or reject shipments from memory vendors, so I decided to do more digging to try and find ground truth.

The first thing I had to do was collect a lot of samples. The key is to attempt to collect both regular and irregular cards in the wild, so I went to the SEG / Hua Qian Bei district and wandered around the gray markets there. I bought about ten memory cards total from small vendors, at prices varying from 30-50 RMB ($4.40 – $7.30), most of them priced toward 30 RMB. The process of shopping for irregular cards itself was interesting. In talking to a couple dozen vendors, you learn a few things. First, Kingston as a brand is weak in China for microSD cards. Sandisk has done a lot more marketing in the microSD space, and as a result, it’s much easier to find Sandisk cards on the open market. The quality of the grey-market Sandisk cards are also typically more consistent. Second, the small vendors are entirely brazen about selling you well-crafted fakes. Typically, the bare cards are just sitting loose in trays in the display case; once you agree on the price and commit to buying the card, the vendor will toss the loose card into a “real” Kingston retail package, and then miraculously pull out a certificate, complete with hologram, serial numbers, and a kingston.com URL you can visit to validate your purchase, and slap it on the back of the retail package right in front of your eyes. Hey, it’s just like new! … I suppose the typical buyer in those markets is not an end user, but someone who is looking to make a quick buck reselling these cards at a hefty markup in a more reputable retail outlet.

One vendor in particular interested me; it was literally a mom, pop and one young child sitting in a small stall of the mobile phone market, and they were busily slapping dozens of non-Kingston marked cards into Kingston retail packaging. They had no desire to sell to me, but I was persistent; this card interested me in particular because it also had the broken “D” logo but no Kingston marking.

Above is a scan of the card and the package it came in (a larger image of the card can be seen below; it is “Sample #4”).

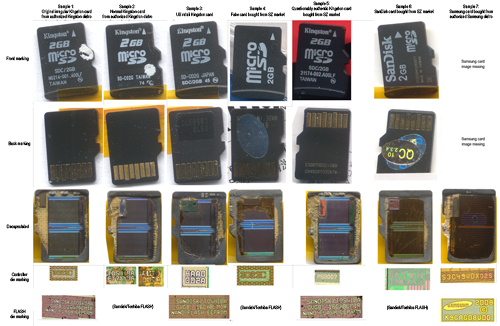

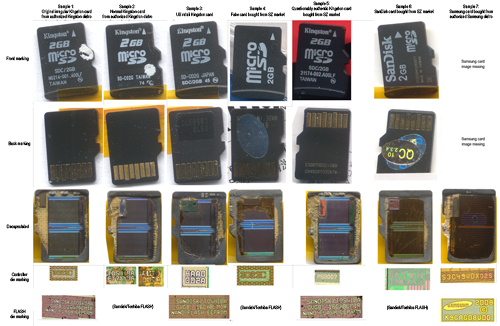

After collecting all the samples, I read out their card ID information, and then digested their packages with nitric acid. Below is the line-up of the cards I digested. Yes, my digestion technique is pretty crude. Actually, most of the damage to the card came from the cleaning process — I was using a Q-tip with acetone to remove the dissolved encapsulant and I had to get a little rough, which doesn’t do any favors for the bond wires. But…good enough for my purposes.

Click on the image above for a full-sized version.

Some notes on the cards above:

Sample 1: This is the original irregular card that got me started on this whole arc. It was purchased through a sanctioned Kingston distributor in China, and to the best of my knowledge, none were shipped to end customers of chumby.

MID = 0x000041, OEMID = 0x3432, serial = 0x960, name = SD2GB.

Sample 2: This is a normal card that I also purchased from the same sanctioned Kingston distributor in China, and is typical of those actually shipped in the first lot of chumby Ones

MID = 0x000002, OEMID = 0x544D, serial = 0x9C62CAE6, name = SA02G

Sample 3: This is a Kingston card purchased through a major US retail chain. Note how the MID and OEMID are identical to sample 2, but not sample 1.

MID = 0x000002, OEMID = 0x544D, serial = 0xA6EDFA97, name = SD02G

Sample 4: This is the aforementioned non-Kingston branded card that I spotted being slapped into Kingston-marked packaging, bought on the open market in Shenzhen. Note the low serial number.

MID = 0x000012, OEMID = 0x3456, serial = 0x253, name = MS

Sample 5: This is a device bought from a more established retailer in the Shenzhen market, but still questionable. I bought it because it had the XXX.A00LF marking, like my original irregular card.

MID = 0x000027, OEMID = 0x5048, serial = 0x7CA01E9C, name = SD2GB

Sample 6: This is a SanDisk card bought on the open market from a sketchy shop run by a sassy chain-smoking girl who wouldn’t stop texting on her mobile. I actually acquired three total SanDisk cards from different sketchy sources but all of them checked out with the same CID info, so I only opened one of them. Interestingly, one SanDisk card turned out to be used and only quick-formatted. With the help of some recovery software, I found DLLs, WAV’s, maps, and verisign certificates belonging to Navione’s Careland GPS inside the drive. A project for another day will be acquiring lots of refurb microSD cards and collecting interesting data off of them.

MID = 0x000003, OEMID = 0x5344, serial = 0x114E933D, name = SU02G

Sample 7: This is a Samsung card that we bought from a Samsung wholesale distributor. I didn’t scan this one before digesting it, so the image of it is missing but the card actually has no markings on the outside — it’s a total blank card with just a laser mark on the back. From appearances alone, it would look to be the sketchiest of the bunch, but in reality it’s one of the best built. Goes to show you can’t judge a book by its cover.

MID = 0x00001B, OEMID = 0x534D, serial = 0xB1FE8A54, name = 00000

That’s a lot of data for a blog post, but I figured more details are better for sharing, since I could find no central database for this kind of information on the web.

Here are the most interesting “high level” results from my survey:

The “normal” Kingston cards (samples #2 and #3) were all direct Toshiba OEM cards (MID = 0x000002, OEMID = 0x544D (ASCII ‘TM’, presumably for Toshiba Memory)). These cards employ Toshiba controllers and Toshiba memory chips, and seem to be of good quality, and thankfully the only ones that were sent on to chumby customers.

The irregular card (sample #1) uses the same controller chip as the outright fake (sample #4) that was bought in the SZ market. Both the irregular Kingston and the fake Kingston had low serial numbers and whacky ID information. Some of these cards experience some difficulty in normal operation. I still hesitate to call Kingston’s irregular card a fake — that’s a very strong accusation to make — but its construction is similar to another card of clearly questionable quality, which leads me to question Kingston’s judgment in picking authorized manufacturing partners.

The irregular card is the only card in the group that does not use a stacked CSP construction. Instead, it uses side-by-side bonding.

The only two memory chip foundries in this sample set were Toshiba/Sandisk and Samsung. Note that Sandisk and Toshiba co-own the fab that makes their memory chips.

Samsung’s NAND die — the most expensive part of a microSD card — is about 17% larger than Toshiba/Sandisk. This means that Samsung microSD cards should naturally carry a slightly higher price than Toshiba/Sandisk cards. However, Samsung does get to offset that against the ability to diversify the same die from microSD packages into street-packaged TSOP devices, and they also don’t have a middleman like Kingston to eat away at margins.

Significantly, Kingston is revealed as simply a vendor that re-marks other people’s chips in its own packaging [clarification]. Every Kingston card surprisingly had a Sandisk/Toshiba memory chip inside, and the only variance or “value add” that could be found is in the selection of the controller chip. Oddly enough, of all the vendors, Kingston quoted with the best lead times and pricing — better than SanDisk or Samsung, despite the competition making all their own silicon and thereby having a lower inherent cost structure. This tells me that Kingston must be crushed when it comes to margin, which may explain why irregular cards are finding their way into their supply chain. Kingston is also probably more willing to talk to smaller accounts like me because as a channel brand they can’t compete against OEMs like Sandisk or Samsung for the biggest contracts from the likes of Nokia or RIMM. Effectively, Kingston is just a channel trader and is probably seen by SanDisk/Toshiba as a demand buffer for their production output. I also wouldn’t be surprised if SanDisk/Toshiba was selling Kingston “A-” grade parts, i.e., parts with slightly more defective sectors, but otherwise perfectly serviceable. As a result, Kingston plays a significant and important role in stabilizing microSD card prices and improving fab margins, but at some risk to their own brand image.

Overall, the MicroSD card market is a fascinating one, a discussion perhaps worth a blog post on its own. I’d like to point out to casual readers that the spot price of MicroSD cards is nearly identical to the spot price of the very same NAND FLASH chips used on the inside. In other words, the extra controller IC inside the microSD card is sold to you “for free”. The economics that drive this are fascinating, but in a nutshell, my suspicion is that incorporating the controller into the package and having it test, manage and mark bad blocks more than offsets the cost of testing each memory chip individually. A full bad block scan can take a long time on a large FLASH IC, and chip testers cost millions of dollars. Therefore, the amortized cost per chip for test alone can be comparable to the cost of silicon itself.

To ground this in solid numbers, suppose a production-grade memory tester costs one million dollars. If you take one million dollars and divide it by the number of seconds over a five year period (a typical depreciation lifespan for such equipment), the equipment “costs” $0.00634 per second. Thus, a thirty second test costs you $0.00634/second x 30 seconds = $0.19. This is comparable to the raw die cost of the controller IC, according to my models; and by making the controllers very smart (the Samsung controller is a 32-bit ARM7TDMI with 128k of code), you get to omit this expensive test step while delivering extra value to customers — I love the fact that when I put on my linux kernel hacker hat, I can be completely oblivious to the existence of bad blocks and use mature filesystems like ext3 instead of JFFS2, at no extra cost to end customers like you. Isn’t it fun to connect the dots, all the way from silicon die markings to the linux kernel to end users, and all the businesses in between?

In the end, I’d have to say that both SanDisk and Samsung look like they might be superior wholesale vendors to Kingston

and Samsung look like they might be superior wholesale vendors to Kingston for memory cards due to their more direct control of their respective supply chains. Unfortunately, you can’t buy Samsung-branded microSD

for memory cards due to their more direct control of their respective supply chains. Unfortunately, you can’t buy Samsung-branded microSD cards on the retail market, as far as I know — Samsung only sells their cards to wholesalers who then rebrand and/or resell the card, and like Kingston these non-OEM brands may blend their vendors so it’s hard to say if you’re getting the best card or simply a usable card.

cards on the retail market, as far as I know — Samsung only sells their cards to wholesalers who then rebrand and/or resell the card, and like Kingston these non-OEM brands may blend their vendors so it’s hard to say if you’re getting the best card or simply a usable card.