Now that’s a memorable factoid. Nature recently published a paper titled “A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure” (Nature 463, 184-190 (14 January 2010), Pleasance et al), which as its title implies, contains the summary of the sequence of a cancer genome derived from a lung cancer tumor. It’s an interesting read; I can’t claim to understand it all. At a high level, they found 22,910 somatic substitutions, 65 insertions and deletions, 58 genomic rearrangements, and 334 copy number segment variations were identified; as I understand it, these are uncorrectable errors, i.e. the ones that got past the cell’s natural error-correction mechanisms. That’s out of about 3 gigabases in the entire genome, or an accumulated error rate of about 1 in 5 million.

I’m not an expert on cancer, but the way it was explained to me is that basically every cell has the capacity to become a cancer, but there are several dozen regulatory pathways that keep a cell in check. In a layman sort of way, every cell having the capacity to become a cancer makes sense because we come from an embryonic stem cell, and tumorigenic cancer cells are differentiated cells that have lost their programming due to mutations, thereby returning to being a (rogue) stem cell. So, a cancer happens when a cell accumulates enough non-fatal mutations such that all the regulation mechanisms are defeated. Of course, this is basically a game of Russian roulette; some cells simply gather fatal mutations and undergo apoptosis. In order to become a cancer cell, it has to survive a lot of random mutations, but then again there are plenty of cells in a lung to participate in the process.

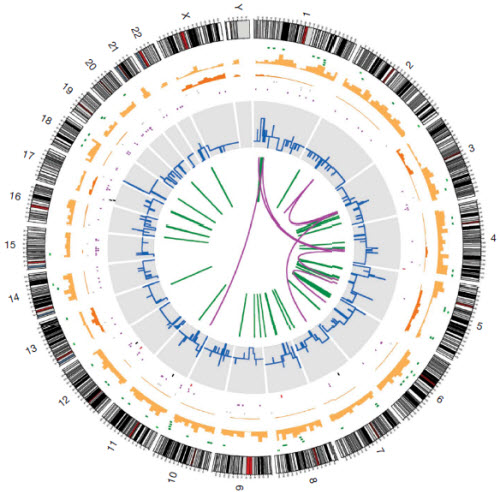

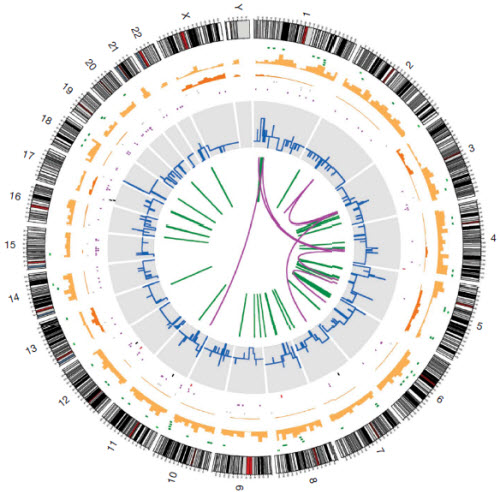

Above: a map of the mutations found in the cancer cell. The 23 chromosomes are laid end to end around the edge of the circle. There’s a ton of data in the graph; for example, the light orange bars represent the heterozygous substitution density per 10 megabases. A higher resolution diagram along with a more detailed explanation can be found in the paper.

The tag line for this post is lifted from the discussion section of the paper, where they assume that lung cancer develops after about 50 pack-years of smoking, which roughly translates to the ultimate cancer cell acquiring on average one mutation every 15 cigarettes smoked. Even though this is an over-simplification of the situation, the tag line is memorable because it makes the impact of smoking seem much more immediate and concrete: it’s one thing to say on average, in fifty years, you will get cancer from smoking a pack a day; it’s another to say on average, when you finish that pack of cigarettes, you are one mutation closer to getting cancer.