I was wandering around on a rainy Saturday afternoon in the mobile phone market in Shenzhen and I spied a stall keeper working on a phone motherboard. Unlike most of the other folks in the market, he was working from a set of schematics — that got my attention. I asked him where he got his schematics from and he kindly dispatched his young son to walk me over to the small tool shop on the other side of the market where, buried underneath a pile of single-use BGA SMT stencils, was a collection of mobile phone schematics for just about every phone made.

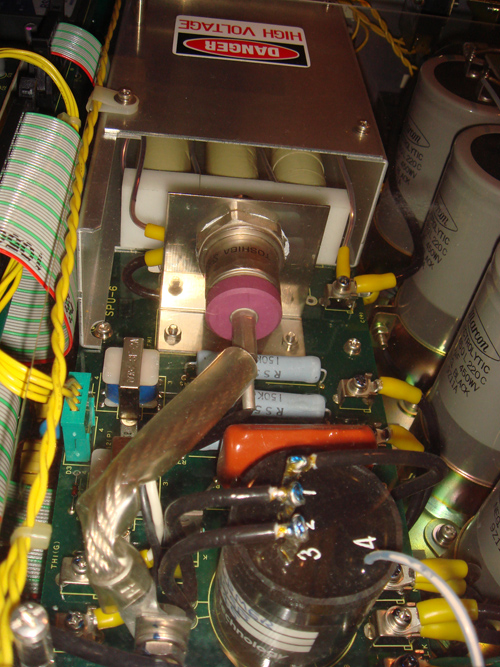

I don’t know about you, but getting my hands on schematics gets me really excited. This is like, the Ultimate Hardware Geek Pr0n. Sure, undressing a mobile phone and revealing its tender innards to my gaze — the sweet perfume of flux residue unleashed, curling into my nostrils — is one level of hardware voyeurism. But, getting the schematics for the phone and peering into its very circuit diagrams — that’s a whole new level, like tearing off the undergarments and ravaging the bosom of the phone. I was excited. I brought the manuals to the clerk and asked how much…wincing at the price I may have to pay to bring these prized morsels back to my hotel room. I breathed a sigh of relief when he asked for only 75 quai — a little over $10 US — for the whole three-book collection. I didn’t even haggle. I grabbed my booty and ran for the nearest taxi.

Alright. Don’t take my double entendre too literally; it’s just fun to write that way. Anyways, on to the manuals…

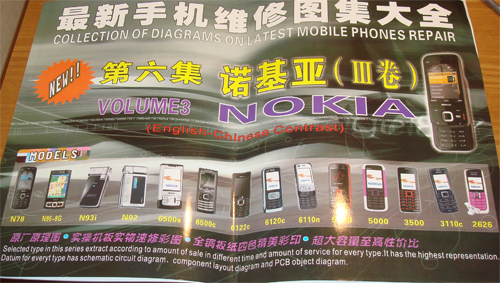

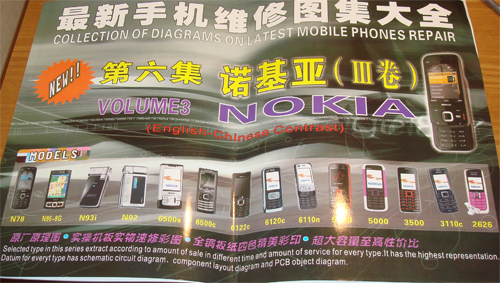

As you can see, these are sold as service manuals.

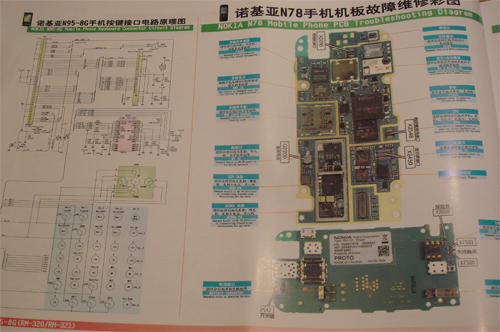

A sample index entry.

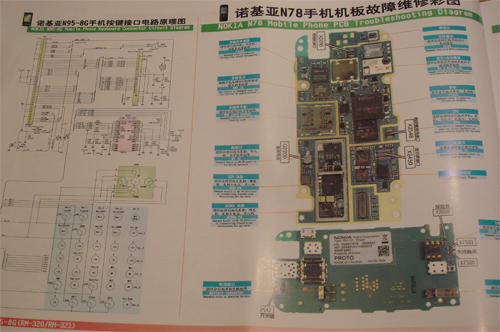

Each phone has a scan of the circuit board that is annotated to call out the position and function of all the components. This helps with the repair process.

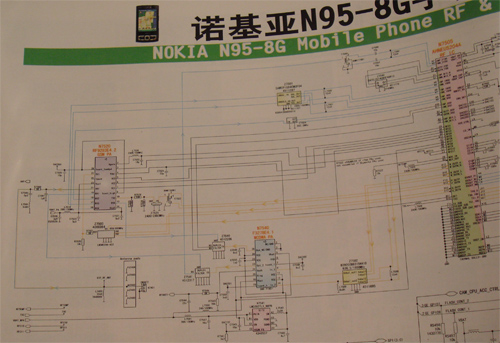

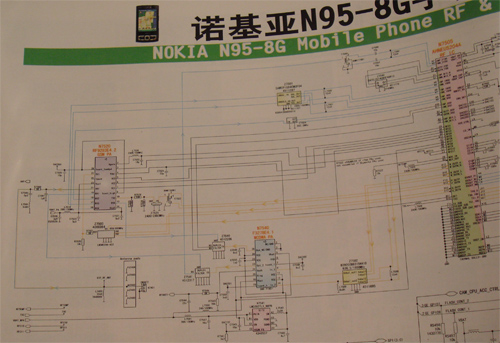

A detail of the schematic for the Nokia N95’s RF section.

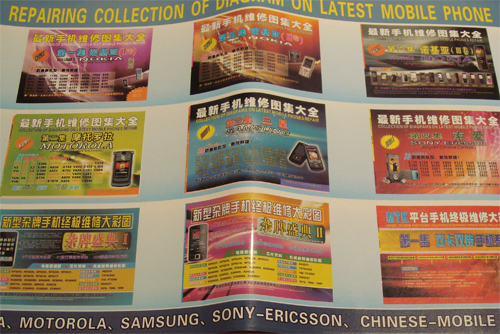

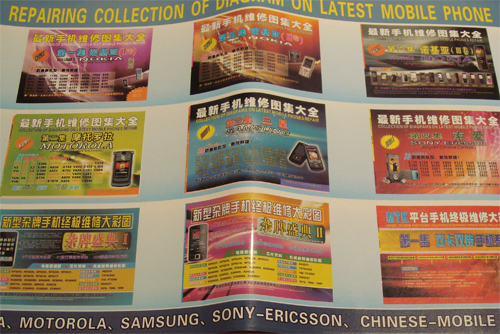

The same publisher of these schematics also offers a wide library of schematics, including those for Samsung, Sony Ericsson, Motorola, and Chinese-local “copycat” phones (like the iPhone clone in the lower left hand corner).

It’s hard to say if these manuals are legitimate (in the sense that Nokia deliberately released the schematics for use as a repair guide), or if they were stolen and republished as a “repair guide”. I doubt, however, that they were reverse-engineered out of the phone, because the schematics contain references to codenames and lingo that would not be embedded directly in the circuitboard. A bit of searching around on Google reveals that these manuals are available for downloads in bits and pieces on various websites, but they all seem to derive from a Chinese origin, and not from Nokia directly.

When I give talks about Open Hardware, I emphasize that it’s fundamentally impossible to keep hardware closed, because the source is the same as the product. Schematics can be derived out of a circuit board layout — a completely legitimate activity under US law. There are shops in China that will pull out a netlist in a couple days for under $1k, and services in the US that will take a bit longer and cost you a lot more. Significantly, there is a whole lot more that goes into building hardware than a mere schematic design: it takes me days to capture a schematic, but it takes me months to get it into mass production. Thus, I believe that publishing a schematic makes the product more serviceable and more useful, yet has little negative effect on your competitiveness in the marketplace. This is a key difference between software and hardware, as the time between writing software and publishing it to “production” can be as short as a few seconds for web-based services.

From my personal perspective, having the schematics is handy for a number of purposes. Aside from satisfying a general curiosity about the phone’s structure, it’s interesting to see the details on how certain sub-circuits are implemented. For example, when I learned electronics at MIT, they never directly taught me how to do EMI mitigation, or ESD protection. While I know the theory behind it, the implementation is trade-craft know how; these are subjects where experience trumps knowledge. Therefore, seeing Nokia’s take on it expands my understanding of the subject.

The schematics are also very useful because of Nokia’s buying power. Picking the cheapest part for a mass-produced hardware design is a tricky exercise; when you leave the realm of buying a few hundred or thousand pieces at a time and move into really high volumes, often times the price of the part has less to do with its design features and more to do with its physical dimensions and who is buying a lot of it. If someone like Nokia is buying millions of a certain part a year, the supply of this part is very stable, lead times are shorter (usually), and the price goes down. So, if you’re a small company and you want to build something cheap, you want to pick parts out of the Nokia supply chain because you indirectly enjoy the benefits of Nokia’s buying power. Thus, these schematics are a good starting point for sourcing cheap parts for production.

Update: got the books for Sony-Ericsson, Motorola, and MediaTek-chipset phones. Found only one Samsung book and it was very out of date. From my observations, the books left on display in these small shops are remainders — typically a little older, perhaps a little less popular. I had to scour the market to find a few of the more recent books, which probably means they are out there but I just don’t know the right person yet. Interestingly, the MediaTek-chipset series of books included some “how-to” manuals on using the chipset to build your own phone. This may be part of the “open” repository of hardware knowledge I previously mentioned in my post about the Shanzhai phone-copiers-turned-innovators.