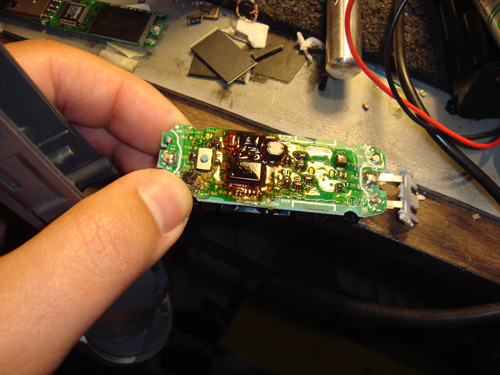

The Ware for March 2009 is a Philips electric shaver. Context is everything, I guess — the people who guessed electric toothbrush were definitely in the right genre of ware, but John H had the benefit of experience in having taken apart and seen the guts of his own Philips electric shaver. The terminals were the give-away that I tried to include, and John H called them out. Congrats, email me to claim your prize!

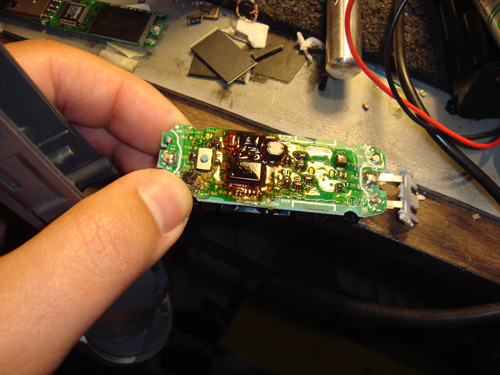

Just so you can see some more context, a larger view of the assembly is below.

Nobody guessed how this ware met its end correctly, but that was an oddball case. It didn’t meet its end drowning in water or meeting a high voltage outlet it didn’t like, nor did it suffer a mechanical jam that overloaded the circuits (although those were good guesses). This one met its end quietly charging on my bathroom counter. The beginning of the end, however, was on the cobblestone streets of Italy, I’m guessing. On my way to Roma Termini, I had to run to catch the train, while dragging my suitcase behind me on the cobblestone streets. The shaver was unfortunately packed near the bottom of the suitcase where it would get the full impact of being dragged across a quarter mile of Italian cobblestone. 24 hours later I got home and tried to use the shaver, and it didn’t work.

I shook the shaver around a bit and the motor briefly engaged, so I figured I’d give it a charge. About a half hour later I come back to the bathroom to find that the shaver is smoking hot! I unplug the shaver right away, but it wasn’t cooling off — I feared the battery was in thermal runaway. I stripped off the casing and sprayed the whole thing down with freeze spray (fortunately I keep such things around). When I inspected the device, it turns out that the battery terminals, which are thin sheets of metal spot-welded onto the ends of the battery, had sheared due to the vibration the shaver was exposed to. Probably some intermittent contact was happening such that the charge circuit behaved badly and caused the battery to overheat, eventually causing the large brown scar you see on the waterproof coating of the circuit board.