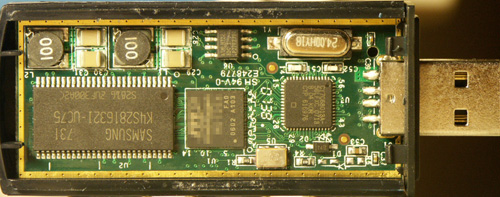

The winner of September 2008’s Name that Ware is Peter Knight, for correctly guessing the ware within one hour of it being posted(!). Congrats, and email me to claim your prize. Thanks again to tmbinc for the user-submitted ware! Along with the submission, he had these interesting comments about the ware:

The reason why I think this is interesting is that this device is in a way unique as that it doesn’t have any other IOs except for USB. It acts truly as a coprocessor, offloading H.264 encoding from the PC. Basically it appears (with the correct software) as a quicktime codec, and allows you for example to recompress DVDs for an iPod much faster than a PC could do. Well, with today’s CPUs, it’s not much faster anymore, but my old PowerBook gets to a pretty decent encoding speed thanks to this gadget. In operation (I sniffed the USB bus for fun), you just upload uncompressed frames, and then read the compressed bitstream back.