Just like the wands from Harry Potter, a good factory chooses you as much as you choose them. Forget the term “vendor” and replace it with “partner”: if you’re doing it right, you aren’t simply instructing the factory; there should be a frank dialog about the trade-offs involved, and how things can be improved. Furthermore, a healthy relationship with a factory can lead to better payment terms, which improves cash flow. In some cases, factory credit can directly replace raising venture capital, taking loans, or Kickstarting. As a result, I treat good factories with the same respect as investors and partners in a business.

Here are some basic things to remember when forming a relationship with a factory.

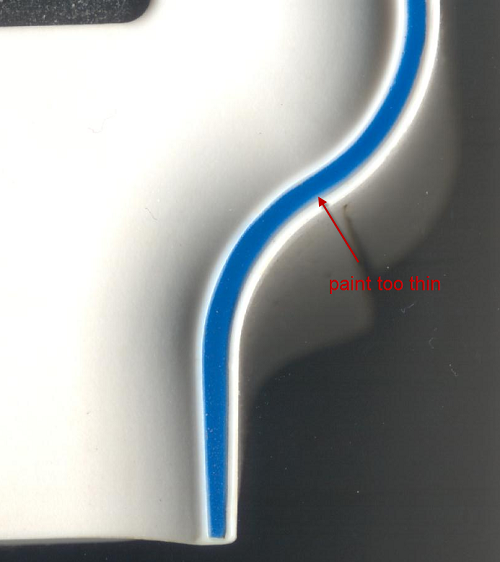

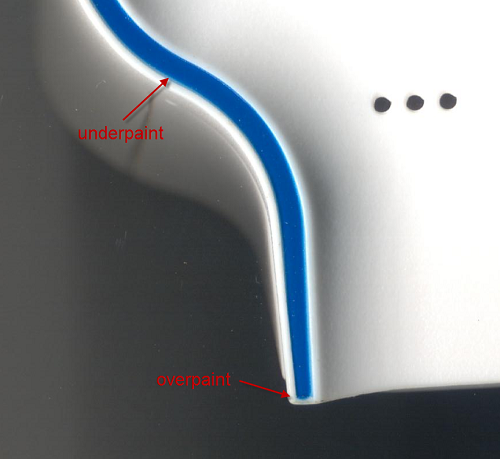

- “It’s easy to know the cost, but hard to know the price“. Cost reduction is critical for any business, but nobody can make up a loss with volume. When negotiating prices with a factory, take a step back and check if everything makes sense. If a quote seems too good to be true, it often is. Factories that lose money on a deal will stop at no end to make it back. Many manufacturing horror stories have roots in unhealthy cost structures – a factory’s first prerogative is survival, even if it means mixing defective units into lots to boost margin, or assigning novice engineers to a flagging project to better monetize their seasoned engineers on more profitable customers.

- “If you can’t talk with the boss, you’re nobody”. Work with a factory too big, and you risk getting lost in bureaucracy, and pushed out of the line at critical times by bigger customers. Work with a factory too small, and they can’t provide the services you need. My rule for right-sizing a factory is to pick the biggest facility where you can get direct access to the lao ban (factory boss) on a regular basis. It’s a good sign if on the first meeting, the lao ban is there to give you a tour and asks astute questions about your business over lunch.

- “Light is the best disinfectant”. If a factory will not quote with an “open BOM”, i.e., a quotation where the cost of every component, process, and margin is explicitly disclosed (not the same use of the word “open” as in the F/OSS context), I won’t work with them. Cost reduction discussions cannot function without transparency; there are too many places to bury costs otherwise. Likewise, if cost discussions seem to be turning into a game of “whack-a-mole” where reduced costs on one line item are inexplicably popping up in another item, run away.

Quotations

A quote should have called out the price of each part, the excess for the job, labor, overhead, and NRE. Here are some of the fine points to understand about quotations that are not immediately obvious:

- “Excess” is the result of what I call the hot dogs-and-buns problem. Hot dogs come in packs of 10, but buns come in packs of 8. So unless one buys 40 servings, there’s going to be left over buns or hot dogs. Likewise, many components come only in 3,000 piece reels, so a 10,000 piece build will conclude with 2,000 pieces of excess (four reels equals 12,000 pieces). “Cut tape” (or partial reels) exist, but the cost per part of cut tape is much higher, as this just shifts the risk of excess material onto the distributor. Excess isn’t all bad – excess can be folded into future runs of a product. So, as long as a decent run rate is sustained, the excess inventory turns into cash on a regular basis. However, at some point production will end or pause, and the bill for the excess will arrive, putting a crimp on cash flow. If a quote is lacking an excess column, it’s possible the factory is charging for the full reel but keeping the excess for their own purposes (this is where many of the gray market goods in Shenzhen come from); or they will just send an unexpected invoice for it down the road. In my opinion, it’s best to get that all out there up front so as to build a complete cradle-to-grave business model.

- Labor costs are devilishly tricky to estimate. However, the good news is that for high tech assemblies, labor is typically a small fraction of total cost. The labor cost of assembling a straightforward board with 200 parts on it in small volumes in China may be about $2-3, whereas the cost of doing it in the US is closer to $20-$30. So even if labor prices double overnight in China and halve in the US, China may still be competitive. This is in contrast to the lower-value goods moving out of China (such as textiles), where the base value of the raw material is already low so labor costs are a significant portion of the final product cost. I usually don’t argue too much over labor costs, since the end result of scrimping on labor is often lowered quality, and pushing too hard over labor costs can force the factory to reduce the worker’s quality of life by trimming benefits.

- Factory margin is also a bit of an art to negotiate. The fair margin for a factory depends on how much value they’ve added, and the volume of production. There are no hard and fast rules for margin. Although I give guidance here, remember there are always exceptions to the rule, and everyone has a special deal that can be cut. Also, the definition of “margin” varies depending on the facility. Some facilities include scrap, handling overhead, and even R&D expense into the “margin”, whereas others may break those out on separate lines, so it’s important to look at the big picture and use some common sense when reviewing a quotation. In general, margin will range between single-digit to low double-digit percentages depending upon volume, value add and project complexity. For very low quantity production lots (~1k pieces) there may also be a per-lot “line fee” charged. This fee partially defrays the cost of setting up an assembly line only to tear it down after running for a short period of time. A line’s throughput may be very fast, producing hundreds to thousands of units a day, but it also takes days to set up.

- NRE, or “non-recurring engineering” – these are one-time fees required to set up a production run, such a stencils, SMT programming, jigs and test equipment. Note that the re-use of test equipment between customers is considered bad practice, so if a multimeter is required as part of a production test, don’t be surprised if a bill for a multimeter is tacked onto the NRE. This is due to customers having drastically varying standards around the maintenance and use of test equipment.

Miscellaneous Advice

Here are a few final parting thoughts to keep in mind.

- Have an understanding of how scrap or exceptional yield loss is handled. There are a few schools of thought around this. Ideally, one only pays for good, delivered items, and the factory bears the burden of defectivity. This gives the factory an incentive to maintain a high production quality, because every percent of defectivity eats away at their margin. However, if the design has a flaw or is too hard to build, and defectivity is high, the factory may start shipping lower quality units as a desperate measure to meet production and margin targets. They may also start gray-marketing defective goods to recover cost, leading to brand reputation problems down the road. It’s good to have some sort of an understanding on how to handle such a contingency ahead of time. This may include, for example, a dedicated “scrap” line item inside the quotation to handle defectivity explicitly.

- On the subject of scrap & yield, it’s a good idea to order more units than the proven demand. These extras go toward handling returns and exchanges. Despite best efforts, mistakes do happen; sometimes they aren’t your fault, such as shipping damage. Ordering 1,000 pieces to fulfill a 1,000 piece Kickstarter campaign means returns and exchanges can be handled with only refunds, as it’s just not practical to fire up the factory to make a dozen replacement units. Thus, as a general rule, I order a few percent excess beyond the customer deliverable, so that I have stock on hand to handle returns and exchanges. Units that don’t get used up by the returns process then turn into demo loaners or business development give-aways to drum up the next set of orders!

- Keep an eye on shipping costs. These fees aren’t typically built into a quotation, but they impact the bottom line (greatly so for low-volume products). Fedex is a great tool to save time, but it’s also a very expensive addiction. Courier fees can easily wash out the profit on a small project, so manage those costs. Pro tip: couriers will offer discounts to frequent shippers, but you have to call in to negotiate the special rates.

- Duties. Keep in mind that components imported to China without an import license are levied a 23% or so automatic duty on their value. The general rule for China is dutiable on import, duty free on export. If stuff is accidentally shipped across the border to Hong Kong, expect to pay a duty to get it back into China. Customs brokers can work the angles – for example, some brokers can get goods taxed by their weight and not their value, which for microelectronics is typically a good deal. I haven’t figured out all the customs rules, as they seem to be a moving target – every month it seems there is a new rule, fine, exceptional fee or tariff to deal with. There are also plenty of shady ways to get goods into China, but I sleep better at night knowing I do my best to comply with every rule. The reason quotations don’t include duties is that it’s assumed by default there will be an import license. Import license enable the duty-free import of goods. However, import licenses cost a few thousand bucks, take weeks to process, and have no room for flexibility, as they are tied to an exact BOM for the product. Small ECOs can invalidate a license – customs officers are known to count the number of decoupling caps on a PCB, and if it doesn’t match the count in the license, a fine is levied and the license is invalidated. Even deviations in the material used to line the decorative box can invalidate a license. This import license scheme favors high-volume produces, and punishes low volume producers.

As one can see, going to China isn’t for everyone. Particularly for those based based in the US, the overhead of courier fees, travel, duties, and late-night concalls adds up rapidly. As a rule of thumb, a US designer is better off assembling PCBs in the US for volumes less than 1k, and they don’t start seeing clear advantages until perhaps 5k-10k volumes. That math shifts in China’s favor as processes such as injection molding and chassis assembly come into play, due to the immense amount of expertise China has accumulated in these labor-intensive processes. Also, the break-even point can be much lower for those living in or near China, as courier fees, travel, and time zone impact are all a small fraction of what they are coming from the US. This compounds with the fact that locals are more effective at leveraging the component ecosystem in China, leading to further cost reductions compared to a design produced using only parts available in the US ecosystem. On the other hand, physically large assemblies or systems built using lots of dutiable components may be cheaper to build domestically, as it saves on shipping costs and tariffs. In the end, one should keep an open mind and try to consider all the possible secondary costs and benefits of domestic vs. foreign production before deciding where to park production.