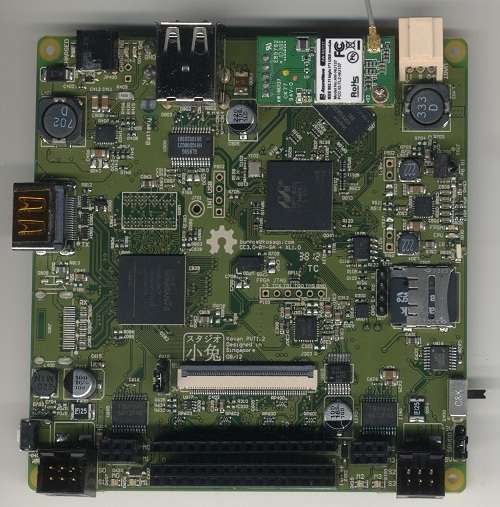

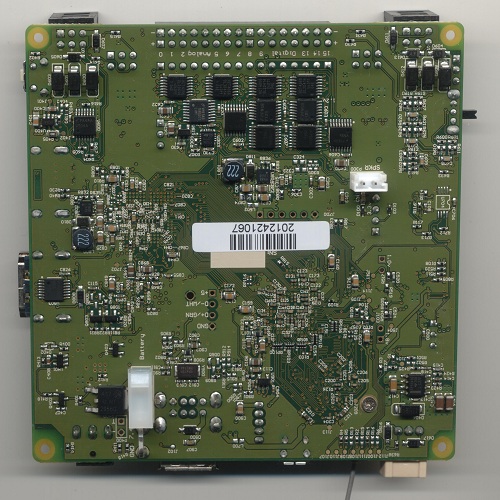

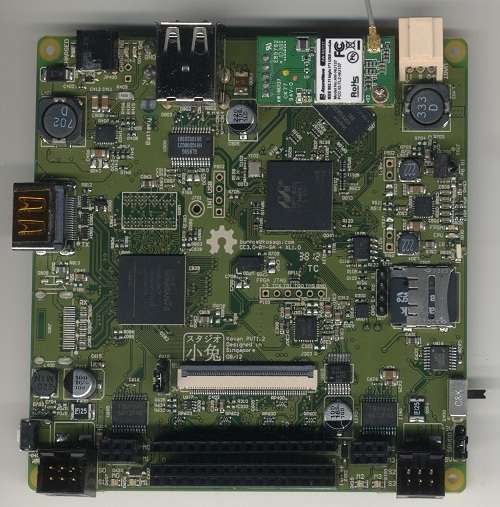

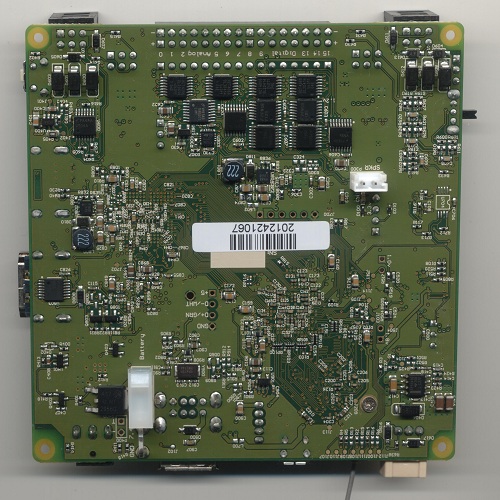

I’ve recently been focusing on making open hardware “reference designs”. Kovan is the codename for a circuit board I designed, intended for autonomous robot control applications (fun fact: all my codenames are metro stops in Singapore). I think Kovan could benefit many niche applications, particularly those that are less cost-sensitive and require a more integrated solution than a cable-spaghetti of daughtercards plus a Raspberry Pi or Beaglebone plus USB dongles.

Kovan is highly integrated, and incorporates features such as an FPGA. The use of an FPGA to interface with the control inputs and outputs offers a unique opportunity for developers to create very precise, low-jitter control loops in VHDL or Verilog, leaving the CPU free to do other tasks. For example, the reference FPGA design uses a system clock of 208 MHz for the servo pulse width controllers, allowing for a 5-nanosecond pulse resolution programmed using 24-bit control registers.

You can grab the source for the hardware through these links: gerbers, schematics in PDF format, 3D STEP model of the circuit board, the native Altium designer source files, and the FPGA source code in verilog. Updates and new developments on the board will be posted and archived at the Kovan wiki.

The next natural question is, of course, ‘how much and where can I buy one?’ This is where things get a little bit unusual. When I release a “reference design”, it means that a third party would market the product. An example of this is the Kickstarted Safecast X geiger counter based upon the geiger counter reference design that I released in January. I’m not producing the geiger counter — International Medcom has instead picked up the design and they are producing and marketing it.

In this case, Kovan is being used by KIPR for the botball educational robotics program. Botball also had a Kickstarter campaign to pre-fund the initial build. Below is the video they produced to promote their product.

While the fully integrated controller won’t be available for sale until early next year through Botball’s store, Adafruit is kind enough to distribute a limited quantity of the motherboards on my behalf in their store. I plan on making a couple dozen boards available to interested developers who can’t wait until the full kit is available through botball. The board alone plus power supply is available for $249, whereas the full botball kit shown in the video above, including LCD, battery, case, software, etc., will go for around $400.

The reference development environment for Kovan is based upon the OpenEmbedded Angström distribution, similar to the system used by the Beaglebone. The firmware version we’re shipping inside the Adafruit boards comes with gcc and Python pre-loaded, so you can get started right away with development — no need to set up cross-compilers. You can download and build your own firmware from source if you want by following this guide. Note that this firmware is different from the one that will be provided with the Botball version, in that this firmware is entirely open source and is targeted toward developers with prior programming experience.

Keeping with a tradition started on this blog long ago, the first user to correctly guess or otherwise determine the number of vias on this circuit board will win a free Kovan board as a prize!

More about the Hardware

Features

Kovan integrates onto a single PCB all the features you need to build a self-guided robot:

Actuator capability

- 4x 1.2A H-bridge motor drivers

- 4x servo drivers

Sensing capability

- 8x 10-bit analog inputs (5v/3.3v gang-selectable input range with individually programmable pull-ups)

- 8x digital I/O (5v/3.3v gang-selectable levels with individually programmable pull-ups)

- Rapid-prototyping headers (each I/O pin has adjacent +/- power rails so as to simplify sensor biasing)

- 3-axis accelerometer

Connectivity

- 802.11b/g wifi

- 2x USB 2.0 ports (suitable for video input via webcam)

- 2x 3.3V UART (one console, one expansion)

- IR rx & demodulator

- IR tx (modulation to be done in FPGA)

UI

- LCD + touchscreen connector (natively supports 3.5″ screen)

- Mono audio output

- Pushbutton and status LED indicators

- Optional digital video output driven by the FPGA (NeTV users might recognize the motif)

Processing

- Linux 2.6.34 running on 800 MHz Marvell ARM w/128 MB DDR2 + 2 GB microSD for firmware storage

- FPGA co-processor enabling hard real-time control extensions & advanced image processing extensions

Battery

- Integrated 2-cell Li-Ion battery charger (C=1.5A)

- Board runs for about 4 hours on a typical 1800mAh 2S1P Lipo RC pack (no motor load condition)

- Battery plug uses Molex rectangular housing 0039013022 (Digikey WM1021-ND) with crimp terminals Molex 0039000207 (Digikey WM3116CT-ND)

- Note: battery or battery emulator required for proper operation – board will not boot otherwise. For battery-less operation, it’s recommended to power the board using a 7.5V power supply (such as Digikey 62-1169-ND) plugged into the battery socket using the above Molex connectors. Do not simultaneously use a battery emulating power supply and a primary power supply, as this would cause the battery charger to attempt to charge the emulating power supply!