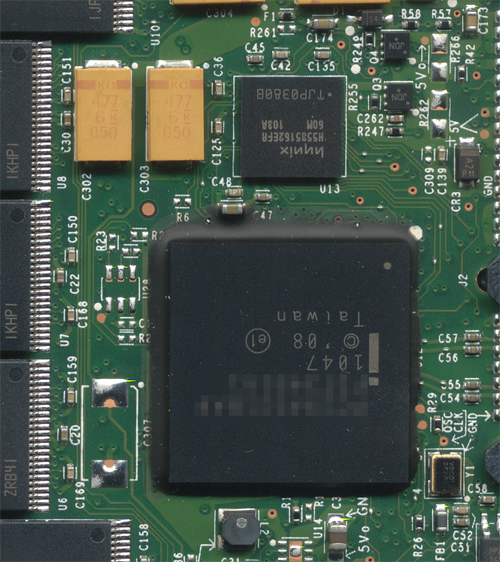

The ware for May 2011 is shown below. Click on the image for a much larger version.

I’ve cropped out about 70% of the circuit board, but I think there are still ample details remaining to enable you to guess this one reliably, probably down to the model and part number. Have fun!

I think it’s interesting how the epoxy underfill on the center BGA has depressions in it to reveal the test points underneath (I think it’s also heartening that they elected to use underfill). I wonder how this was accomplished. Underfill is chosen specifically to have good wetting properties, and it cures hard. So, the only way I can think of making those depressions in to attach a jig that’s present while the underflow cures. Seems like a lot of effort for two test points, one of which could be easily moved to a zone outside of the underfill’s reach.

Also, to readers unfamiliar with underfill — a number of people have shown me boards with underfill on them, and have incorrectly identified the underfill as an anti-tamper security measure. While underfill does make it harder — although not impossible — to remove the chip, the technology was not developed primarily for security. Underfill exists because BGAs have a tendency to delaminate and crack off of the PCB, resulting in reliability issues over time. The mechanism can be due to vibration, shock, flexing, or thermal cycling. Thermal cycling is a natural result of warming and cooling due to turning the device on and off. The chip package and the mating board grow and shrink at different rates due to different coefficients of thermal expansion. This causes the solder balls to undergo a mechanical stress that can eventually lead them to shear or crack. The Xbox360, for example, lacks underfill on the GPU, and this could be a contributing factor to the infamous “Red Ring of Death” issue.

Underfill is quite standard on all manner of gadgets that can be carried about, flexed, dropped, and/or subject to vibration. However, underfill is devilishly tricky to apply correctly. If air pockets are trapped during the application of the underfill, it can actually make the problem worse by concentrating all the stress in the air pockets. Hence, the epoxy used for underfill in uniquely engineered and (if your factory is doing it right) applied by a robot to ensure that no air is trapped in the gap underneath as it flows underneath the soldered-down BGA. Which leads to why I find the test points poking through the underfill to be interesting, because the epoxy should have flown right over the bumps, even if it was temporarily displaced for testing prior to curing; and after curing, the epoxy should be rock-hard and impenetrable to test probes.