How cheap can you make a phone?

Recently, I paid $12 at Mingtong Digital Mall for a complete phone, featuring quad-band GSM, Bluetooth, MP3 playback, and an OLED display plus keypad for the UI. Simple, but functional; nothing compared to a smartphone, but useful if you’re going out and worried about getting your primary phone wet or stolen.

Also, it would certainly find an appreciative audience in impoverished and developing nations.

$12 is the price paid for a single quantity retail, contract-free, non-promotional, unlocked phone — in a box with charger, protective silicone sleeve, and cable. In other words, the production cost of this phone is somewhere below the retail price of $12. Rumors place it below $10.

This is a really amazing price point. That’s about the price of a large Domino’s cheese pizza, or a decent glass of wine in a restaurant. Or, compared to an Arduino Uno (admittedly a little unfair, but humor me):

| Spec | This phone | Arduino Uno |

|---|---|---|

| Price | $12 | $29 |

| CPU speed | 260 MHz, 32-bit | 16 MHz, 8-bit |

| RAM | 8MiB | 2.5kiB |

| Interfaces | USB, microSD, SIM | USB |

| Wireless | Quadband GSM, Bluetooth | – |

| Power | Li-Poly battery, includes adapter | External, no adapter |

| Display | Two-color OLED | – |

How is this possible? I don’t have the answers, but it’s something I’m trying to learn. A teardown yields a few hints.

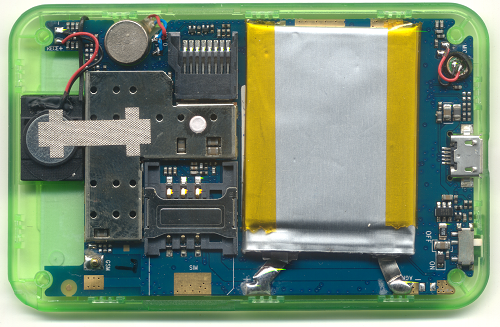

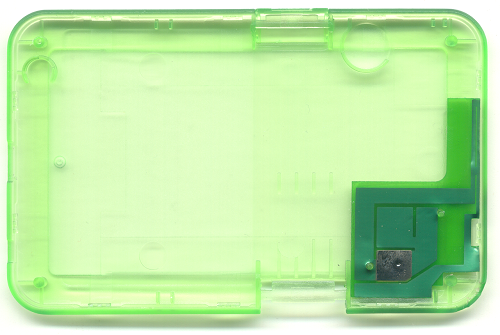

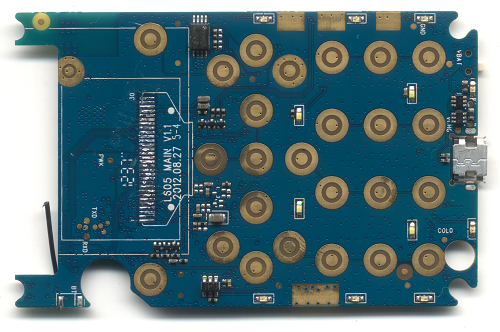

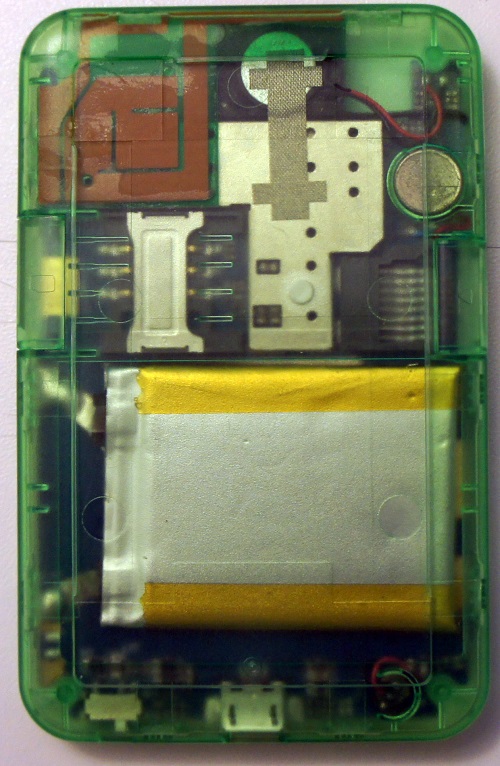

First, there are no screws. The whole case snaps together.

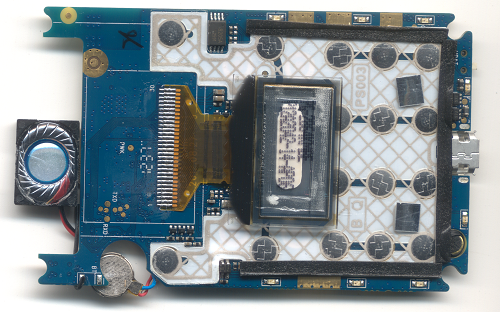

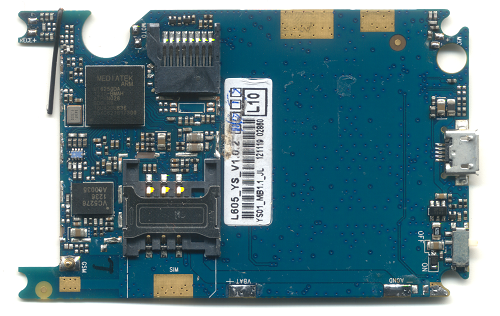

Also, there are (almost) no connectors on the inside. Everything from the display to the battery is soldered directly to the board; for shipping and storage, you get to flip a switch to hard-disconnect the battery. And, as best as I can tell, the battery also has no secondary protection circuit.

The Bluetooth antenna is nothing more than a small length of wire, seen on the lower left below.

Still, the phone features accoutrements such as a back-lit keypad and decorative lights around the edge.

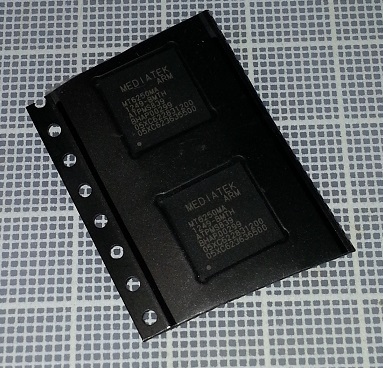

The electronics consists of just two major ICs: the Mediatek MT6250DA, and a Vanchip VC5276. Of course, with price competition like this, Western firms are suing to protect ground: Vanchip is in a bit of a legal tussle with RF Micro, and Mediatek has also been subject to a few lawsuits of its own.

The MT6250 is rumored to sell in volume for under $2. I was able to anecdotally confirm the price by buying a couple of pieces on cut-tape from a retail broker for about $2.10 each. [No, I will not broker these chips or this phone for you…]

That beats the best price I’ve ever been able to get on an ATMega of the types used in an Arduino.

Of course, you can’t just call up Mediatek and buy these; and it’s extremely difficult to engage with them “going through the front door” to do a design. Don’t even bother; they won’t return your calls.

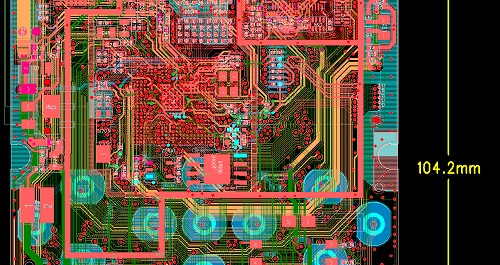

However, if you know a bit of Chinese, and know the right websites to go to, you can download schematics, board layouts, and software utilities for something rather similar to this phone…”for free”. I could, in theory, at this point attempt to build a version of this phone for myself, with minimal cash investment. It feels like open-source, but it’s not: it’s a different kind of open ecosystem.

Introducing Gongkai

Welcome to the Galapagos of Chinese “open” source. I call it “gongkai” (公开). Gongkai is the transliteration of “open” as applied to “open source”. I feel it deserves a term of its own, as the phenomenon has grown beyond the so-called “shanzhai” (山寨) and is becoming a self-sustaining innovation ecosystem of its own.

Just as the Galapagos Islands is a unique biological ecosystem evolved in the absence of continental species, gongkai is a unique innovation ecosystem evolved with little western influence, thanks to political, language, and cultural isolation.

Of course, just as the Galapagos was seeded by hardy species that found their way to the islands, gongkai was also seeded by hardy ideas that came from the west. These ideas fell on the fertile minds of the Pearl River delta, took root, and are evolving. Significantly, gongkai isn’t a totally lawless free-for-all. It’s a network of ideas, spread peer-to-peer, with certain rules to enforce sharing and to prevent leeching. It’s very different from Western IP concepts, but I’m trying to have an open mind about it.

I’m curious to study this new gongkai ecosystem. For sure, there will be critics who adhere to the tenets of Western IP law that will summarily reject the notion of alternate systems that can nourish innovation and entrepreneurship. On the other hand, it’s these tenets that lock open hardware into technology several generations old, as we wait for patents to expire and NDAs to lift before gaining access to the latest greatest technology. After all, 20 years is an eternity in high tech.

I hope there will be a few open-minded individuals who can accept an exploration of the gongkai Galapagos. Perhaps someday we can understand — and maybe even learn from — the ecosystem that produced the miracle of the $12 gongkai phone.