First, a heartfelt “thank you” to all those who have backed our crowdfunding campaign to bring Novena-powered open computing devices to the world. xobs and I are very flattered to have reached almost 70% of our goal already.

One excellent outcome of the campaign is a lot of people have reached out to us to extend the Novena platform and make it even better, and so we’re offering a diverse range of stretch goals to provide an even better open laptop for all walks of users.

Stretch #1: Partnering with Jon Nettleton for Open 2D/3D Graphics Drivers on Novena: +$50k ($300k total)

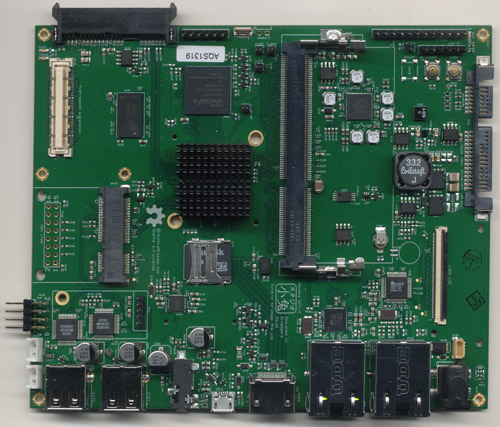

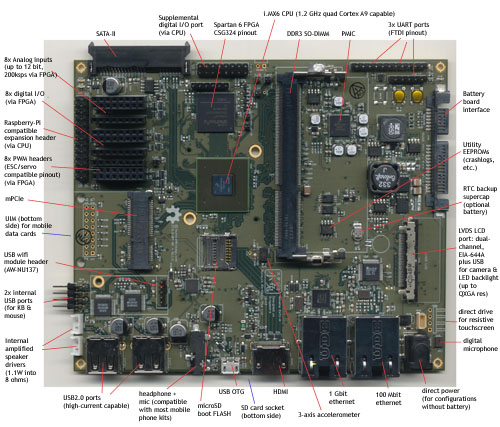

We designed Novena to be the most open platform we could practically build. The hardware blueprints and software source code are available for download. The entire OS is buildable from human-readable source, and requires no binary blobs to boot and run well.

However, there are elements of the i.MX6 SoC that lie dormant, due to a lack of open source drivers. In particular, the 2D/3D graphics accelerator in the i.MX6 has closed-source drivers. While we don’t force you to use these closed-source drivers, a major impediment to us being “libre” is the lack of open source drivers for these components.

We’re excited to announce a partnership with Jon Nettleton, an expert on Linux graphics drivers, to enable this crucial piece of the libre puzzle. Here is a short statement from Jon Nettleton himself on the prospect:

Novena Backers and OSS enthusiasts,

I am very pleased to announce myself, Jon Nettleton (a.k.a. jnettlet, linux4kix), as a stretch-goal partner for the Novena Project. I will be taking on the task of assuring that the shipping Novena platforms will not require a binary userspace driver for 2D/3D graphics acceleration. Utilizing my experience working on Linux graphics drivers along with my strong community involvement, I will be making sure that contributing developers have everything they need to keep the Etnaviv driver project moving forward.

To accomplish this we are requesting an additional $10,000 of funding. This additional capital will be used to not just fund my development effort, but to also provide incentives for other contributing developers. It will also benefit me the time to coordinate with other hardware vendors interested in supporting an open source graphics driver implementation for the Vivante chipset, and getting them involved. There is no “US“ and “THEM” in this effort. “WE” will bring to fruition a modern graphics accelerated desktop platform for the Novena Project.

Therefore, if we can raise $50k over our original target of $250k, we will donate the $10k that Jon needs for the effort for providing open 2D/3D graphics drivers for the Novena platform. The remainder of that raised will be used to help cover the costs of building the hardware you ordered.

Significantly, since this is an open source effort, everyone in the i.MX6 community can benefit from the outcome of this funding. Because of this, we’ve added a “Buy Jon a Six Pack ($30)” pledge tier (capped at 417 pledges) so that existing i.MX6 users who want to contribute toward this goal without buying our hardware can participate. For every dollar contributed to this pledge tier, we will give Jon Nettleton at least 80 cents, regardless of our ability to reach the first stretch goal. The other ~20 cents go toward compulsory campaign operation costs and financial operator transaction fees.

Stretch #2: General-Purpose Breakout Board: +$100k ($350k total)

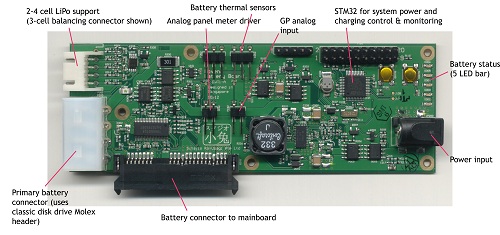

We include a FPGA and a nice high-speed connector, but many users just want to toggle a GPIO or take a simple analog reading without having to design and build a PCBA from scratch. If we can raise an additional $50k over the previous stretch goal, we will include a General Purpose Breakout Board (GPBB) with every piece of hardware we ship.

The GPBB buffers 16 FPGA outputs and 8 FPGA inputs to be compatible with either 3.3V or 5V, gang-selectable via software. It also provides six 10-bit analog inputs (up to 200ksps sample rate) and two 10bit analog outputs (~100ksps max rate), all broken out to an easy-to-use 40-pin male 0.1″ dual-row header.

The GPBB is handy for all kinds of control and sensing situations. Because the GPBB is backed by a powerful FPGA, each of the buffered FPGA output lines can be programmed for a wide range of applications. For example, an FPGA output could be configured as a precision PWM channel with hard-real time feedback control for demanding robotics motor driver applications. Or it can be used to interface with bespoke serial protocols, such as those found in modern LED strip lighting.

For user who don’t want to muck with FPGA code and prefer to grapple a GPIO from the command line, we have user-space drivers for the board prepared in Linux, through a combination of the Linux GPIO API, and the Linux I2C API. As a result it’s a snap to script up simple applications using your favorite high level language.

Significantly, the GPBB isn’t vaporware — we developed this board originally for use as a breakout for production testing circuit stickers from our Chibitronics product line. At this very moment, the GPBB design is being used to drive mass production of circuit stickers.

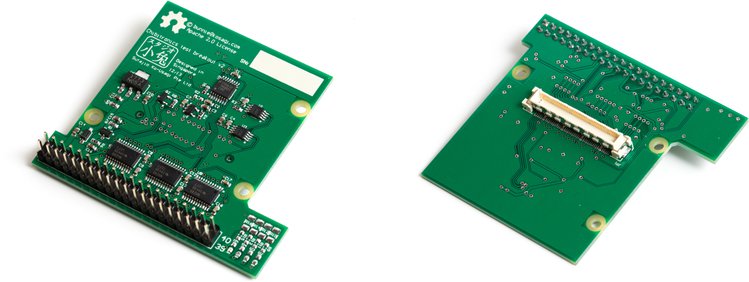

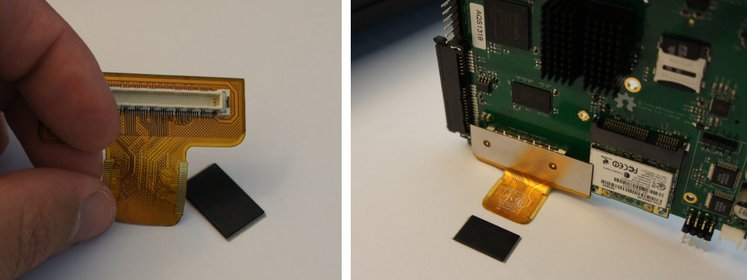

Stretch #3: ROMulator Breakout Board: +$150k ($400k total)

We designed Novena to be a versatile hacking tool. Case in point, last December we reported results at 30C3 revealing a secret knock that can allow arbitrary code execution on select SD card controllers. We discovered this in part with the assistance of Novena.

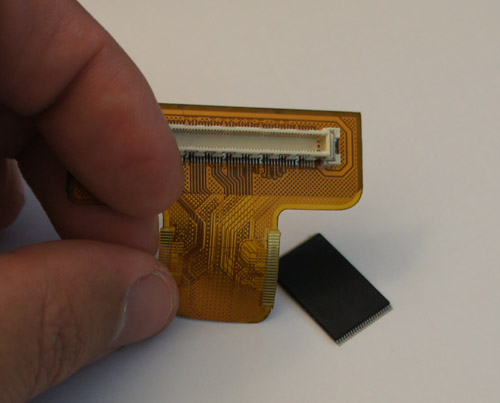

We used Novena as a ROMulator — a FLASH ROM emulator. For this application, we developed a flexible PCB that’s so thin, it can be soldered in between a TSOP FLASH ROM and the underlying PCB. In this mode, we can use the FPGA built into Novena to snoop the traffic going to and from the FLASH ROM.

Alternately, the FPGA can be used to emulate a ROM device using its local 256 MiB of DDR3 memory. Since the DDR3 controller implementation is multi-ported, during ROM emulation one can inspect and modify the ROM contents on the fly without disrupting target operation. This has a number of powerful applications, from ToC/ToU attacks to speeding up firmware development on devices that load from NAND.

If we can raise an additional $50k over the previous tier, we’ll include a ROMulator Breakout Board (in addition to the General Purpose Breakout Board) with every piece of hardware shipped.

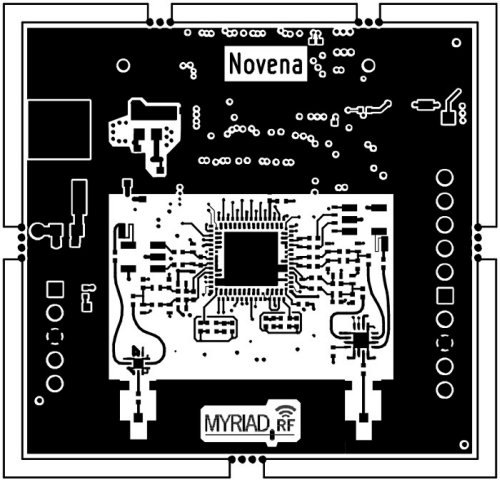

Stretch #4: MyriadRF Software Defined Radio: +$250k ($500k total) or >200 backers for the desktop/laptop/heirloom version

Software! Defined! Radio! We’re very excited to offer the possibility of teaming up with MyriadRF, to provide a custom-made SDR solution for Novena. Their open hardware SDR solution operates in all the major radio bands, including LTE, CDMA, TD-CDMA, W-CDMA, WiMAX, 2G and many more.

The retail price of the MyriadRF is $299, and MyriadRF has graciously pulled strings with their fabrication partner and enabled a low minimum order quantity of 200 units to build this custom version for Novena. If we can clear a total raise of $500k or at least 200 total backers for the desktop/laptop/heirloom version, we’ll include with every desktop/laptop/heirloom version a MyriadRF SDR board. Since the MyriadRF is such a high ticket-item, only desktop and higher tiers are eligible to receive this reward.

Significantly, the MyriadRF extends beyond the front of the Novena case, so part of the money from this tier is going toward buying the extra tooling to provision a removable panel on the front edge of the case, so that when the SDR module is installed it can comfortably hang out of the case, giving easy access to the U.FL RF connectors.

If you find these stretch goals exciting and/or useful, please visit our campaign page and join the community helping to bring open hardware to the world, and please help us spread the word!